0 saved

0 saved

33.1K views

33.1K views

Yes, we appreciate the irony and meta nature of having a mental model to explain mental models but… well, we're going there.

Mental Models are simplified representations, concepts, and frameworks that allow us to quickly understand ourselves and our world.

AN INSTINCTIVE TOOL FOR A COMPLEX WORLD.

Mental Models ultimately exist because our world and life are incredibly complex, and our brains have limited ability to hold that complexity — so we make sense of everything and act in the world with the cognitive shortcuts that are Mental Models.

Everyone uses Mental Models to simplify and understand everything, all the time. They define the way you interpret, prioritise, decide, anticipate, predict, and engage with the world and yourself. See the In Practice section below for examples from a range of domains.

4 TYPES OF MODELS.

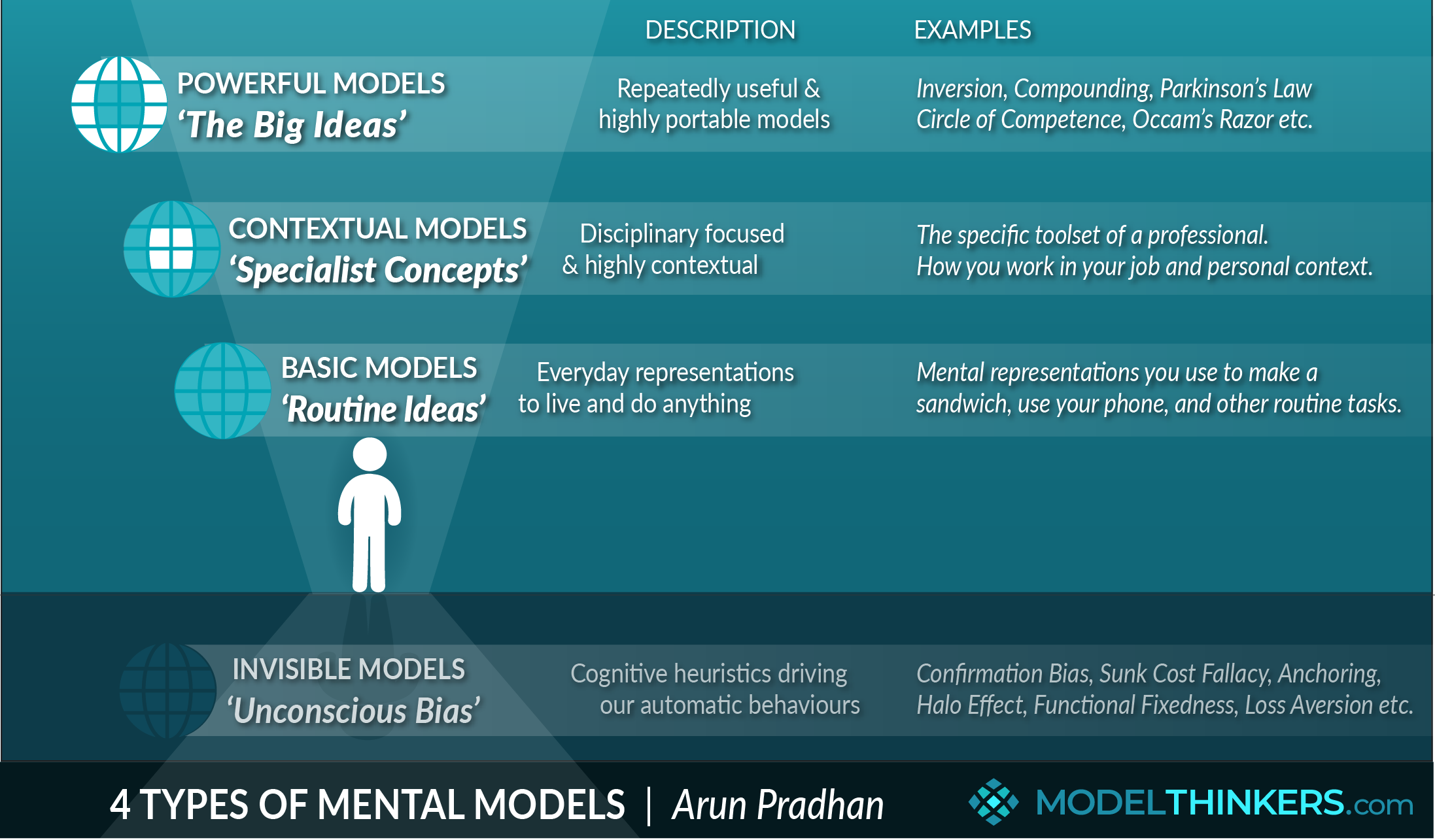

At the risk of getting way too meta, our mental model about mental models identifies 4 types of models:

-

The invisible models. The heuristics, mental shortcuts, and cognitive biases that rule our decisions when our more conscious brain isn’t paying attention — which is almost all the time. E.g. Confirmation Bias, Anchoring and so many more.

-

The routine models. The models we take for granted as we navigate through the basics of our existence. E.g. the mental representations we rely on when making a sandwich, drive a car, and walk through our house.

-

The contextual ones. These might be developed through specialist study or cycles of personal experience and reflection in your context. They help us to act in our specific environment and/or domain. E.g. the nuts and bolts of a profession, such as how a radiologist interprets and acts on medical imaging; or a personal lesson that might have limited transferability, like how to work with your specific boss who tends to be moody on Tuesdays, but open to ideas that reference statistics etc.

-

And finally, there are the powerful models and tested transferable ‘big ideas.’ These are the mental models that are repeatedly useful for many people and highly applicable across varying contexts and domains. Browse through ModelThinkers for many examples.

MENTAL MODELS AND MODELTHINKERS.

Here at ModelThinkers, we focus on delivering the most useful and transferable models — so we cover the powerful and invisible models. We have been inspired by Charles Munger's approach to building a Latticework of Mental Models and are acutely aware that there are limits to all models, explore Map versus Territory model for more (that's why we've included a 'Limitations' section on every summary).

- Bring awareness to your mental models.

Metacognition is the process of ‘thinking about thinking’, and is an important part of developing high performance in any domain. This includes reflecting on what your current mentals models are in any situation, challenge or decision.

- Remember that the Map is not the Territory.

We’ve dedicated a mental model to this here, but the point is that all mental models are merely representations of reality. It’s important to remember that all mental models are ultimately wrong and that several, even opposing, mental models might have elements of truth at the same time.

- Understand other people’s mental models.

Appreciate that other people won’t necessarily share your mental models and will interpret a situation differently. Rather than assuming that they are wrong, ask questions to better understand the mental models that led to that understanding, then challenge your own mental models with that understanding.

- Consciously build and apply a latticework of mental models.

This is the point of ModelThinkers and is covered more by the Munger’s Latticework of Mental Models.

The main limitation of mental models is that they are not reality, as explored by the Map vs Territory.

The blind men and the elephant.

In the parable of the blind men and an elephant, a group of blind men come across an elephant, having no existing experience (and therefore mental models) of what an elephant is. They each reach out, touching a different part of the elephant. One touches the tusk and says “this is a thick snake.” Another touches it’s ear and claims that it is a fan.

Plato’s cave.

The allegory of the cave by Plato described prisoners chained in a cave who can only see a wall. On the wall is the projected shadows of activity of people behind them. They never see the actual people, just the shadows — which they mistake for reality.

In this sense, shadows can be seen as metaphors for mental models — an interpretation of reality. However, the parable is more generally used to make a distinction between trusting our senses versus philosophical reasoning.

The desktop on your computer.

Want a more grounded example? Consider how computers make use of the desktop metaphor to explain how ‘files’ fit in ‘folders’ and how to navigate options within a digital environment. This metaphor leverages existing metaphors of a real-world workspace to present a meaningful and efficient user experience.

Domain views of Mental Models.

Mental Models have been discussed and used in a number of fields.

- Psychology and philosophy: mental models refer to mental representations or imagery;

- UX design and usability: mental models are a key tool in understanding user assumptions, behaviour and expectations;

- Education: mental models are used to understand prior knowledge and build on a learner's existing conceptual framework.

- Learning and performance: mental models were identified by Peter Senge as one of five key ingredients of a learning organisation.

- Business: Charles Munger and the Latticework of Models approach that lies behind ModelThinkers.

Mental models are the underlying model that informs everything in this site, so in that sense it’s linked to everything. That said, the two models to particularly consider in relation to it are Munger’s latticework and map vs territory.

The concept behind mental models were explored by philosopher and mathematician Charles Pierce in 1896, who incorporated a ‘diagram’ or representation of things as part of a broader reasoning process. After that, in 1927, Georges-Henri Luquet argued that children construct ‘internal models’.

The idea of mental model was explicitly referred to by Kenneth Craig in his 1943 book, The Nature of Explanation where he described the mind creating “small scale models.”

The term ‘mental models’ came to the fore in 1983 when Phil Johnson-Laird published a book called Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference and Consciousness.

My Notes

My Notes

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”