0 saved

0 saved

37.4K views

37.4K views

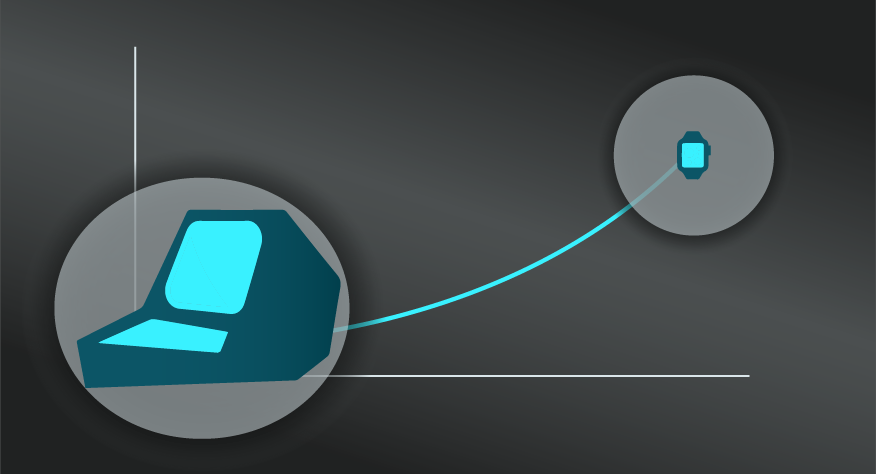

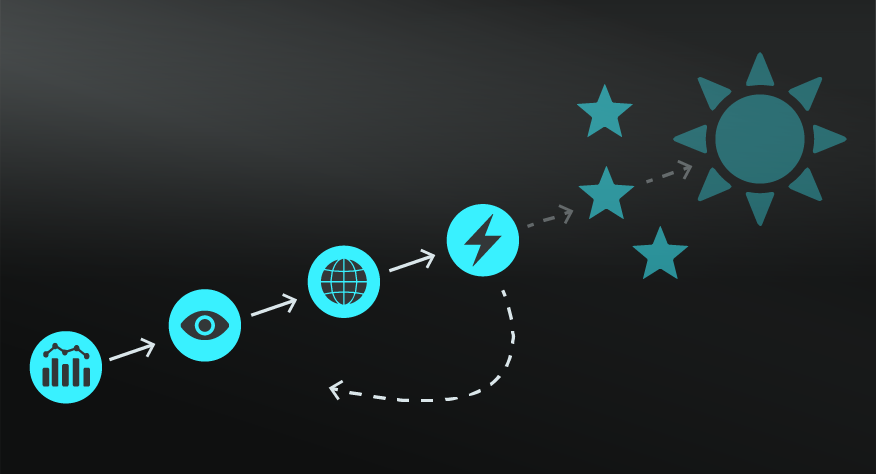

Continued digital disruption and the rise of automation has required people to develop complex skills more often and faster than ever before. A key way of achieving this is using deliberate practice.

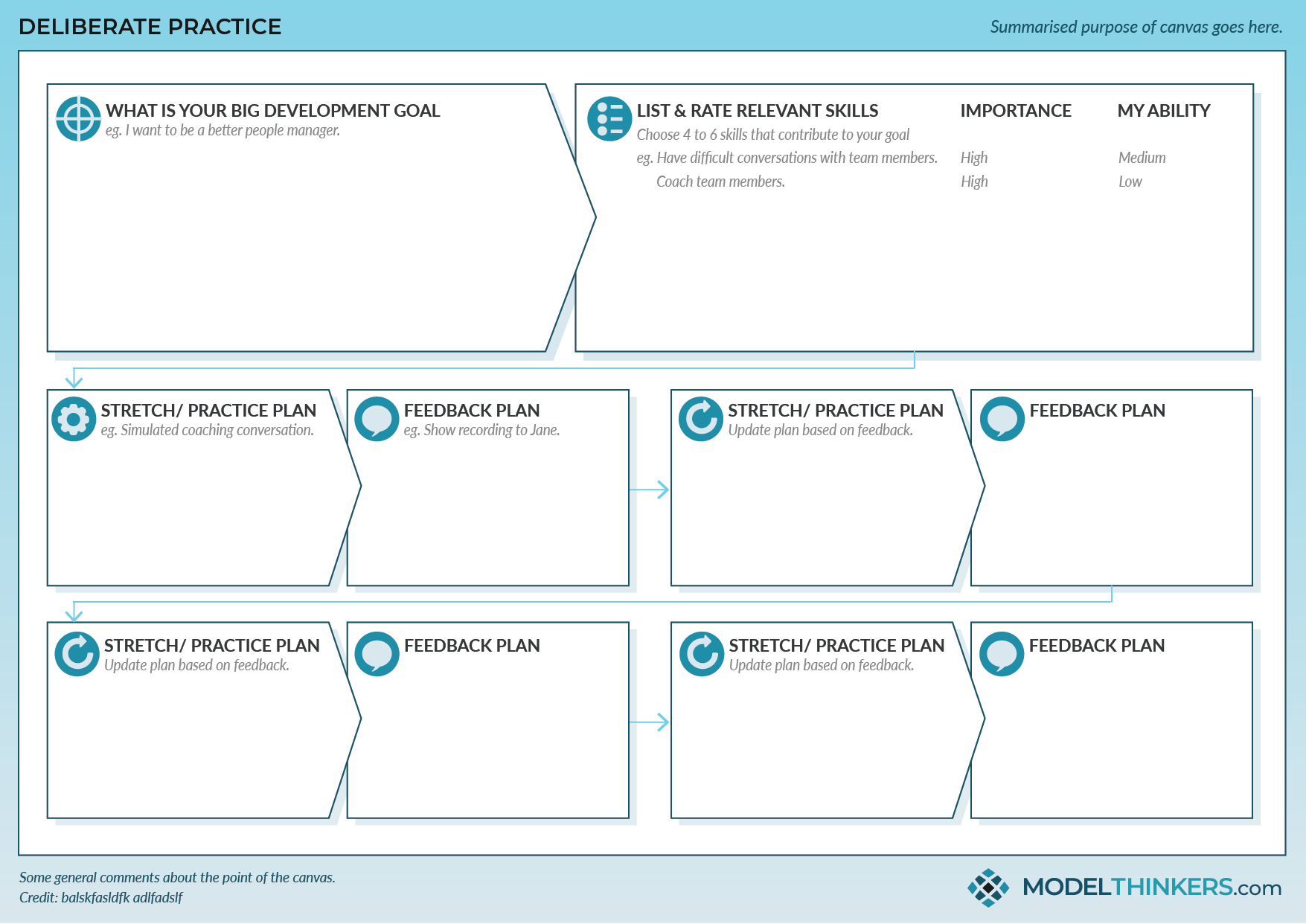

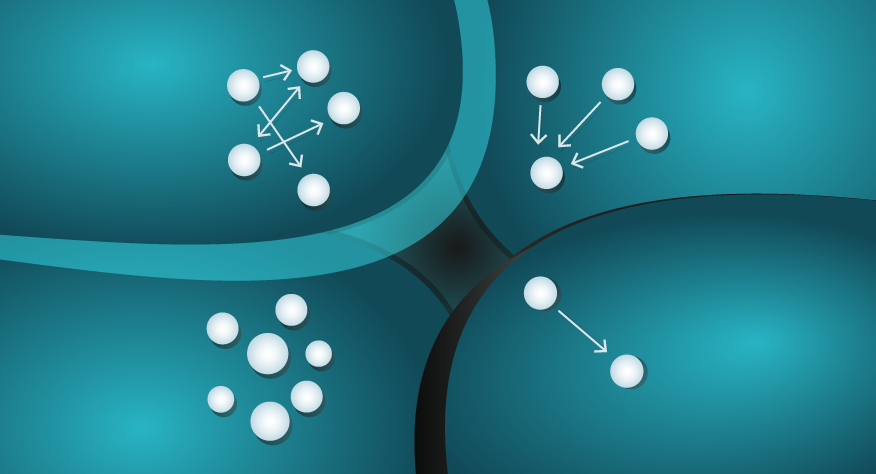

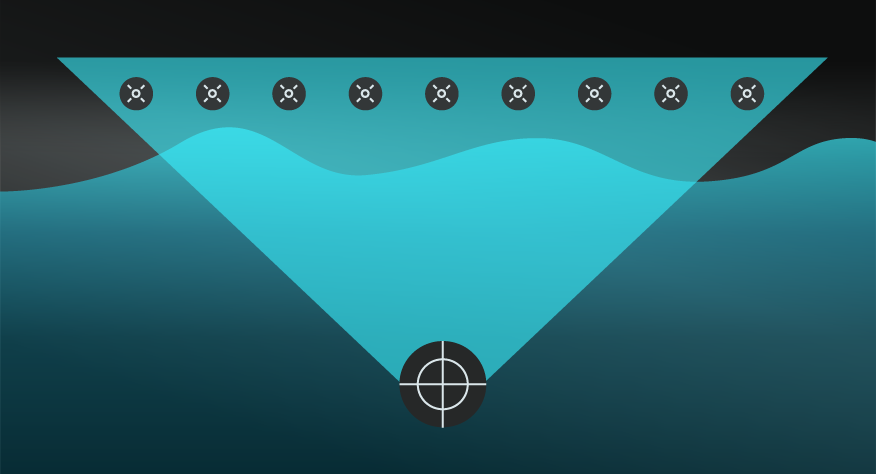

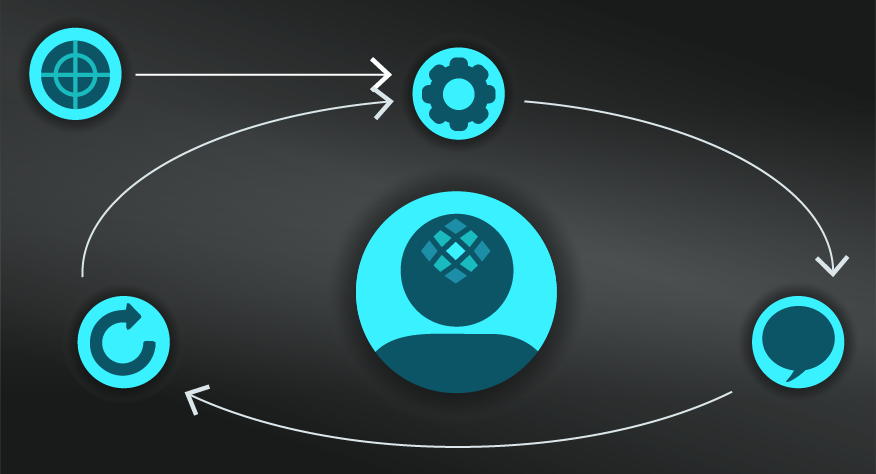

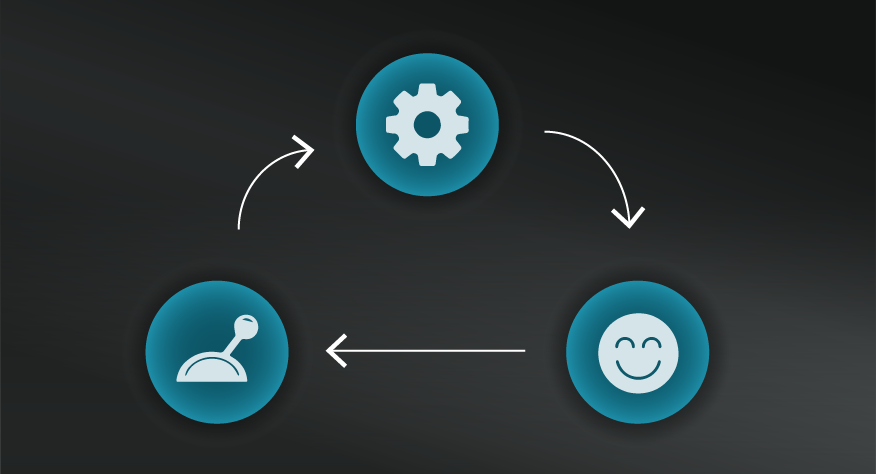

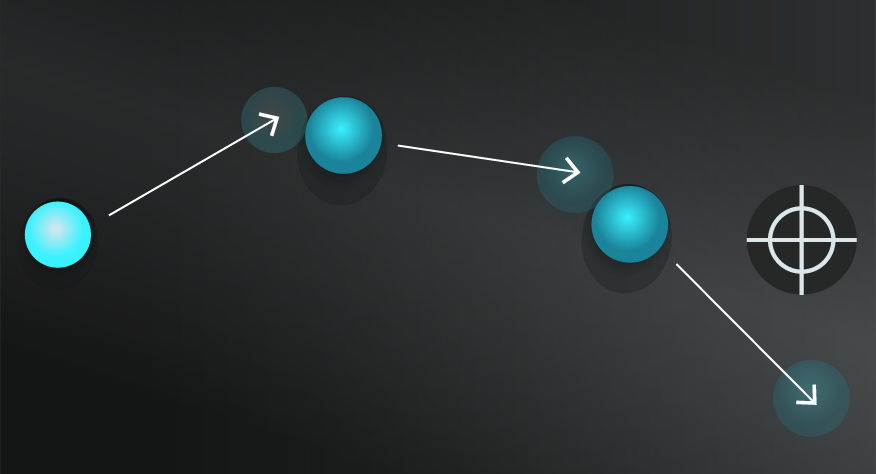

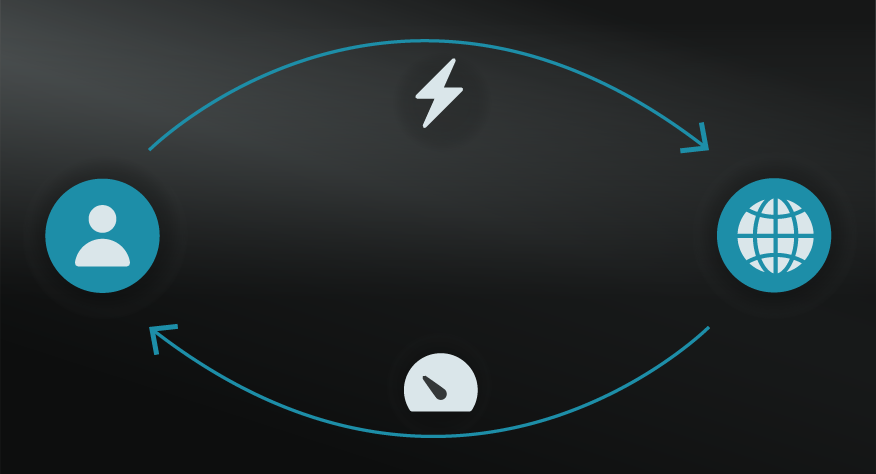

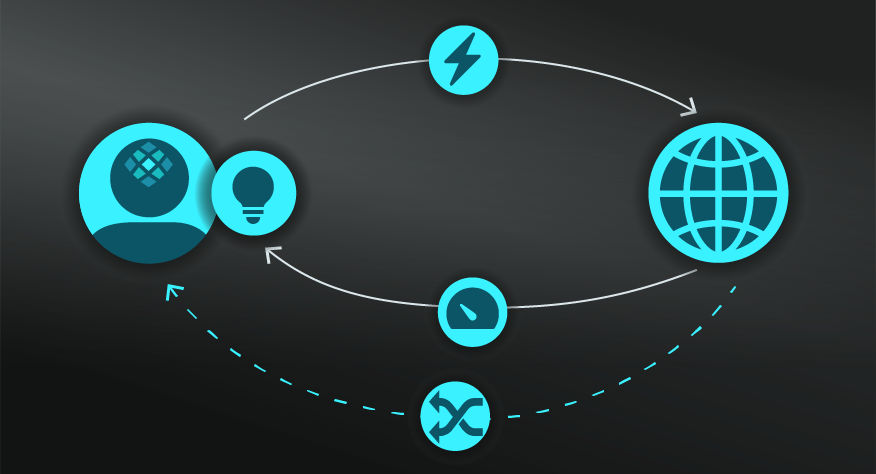

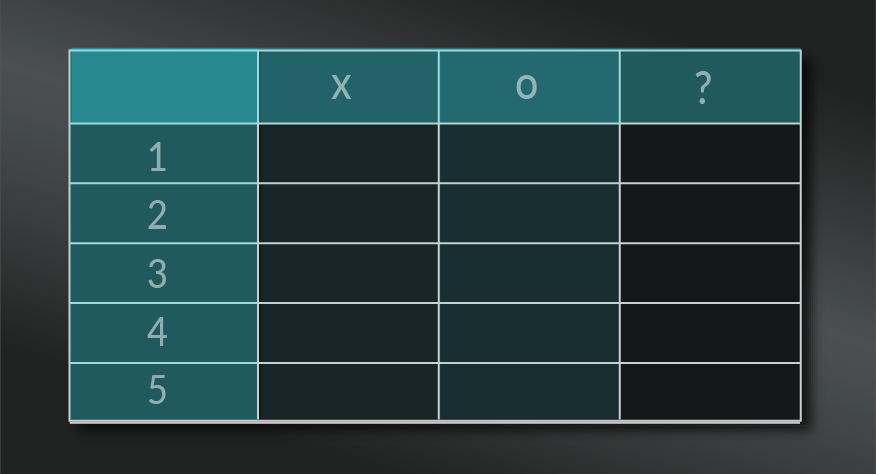

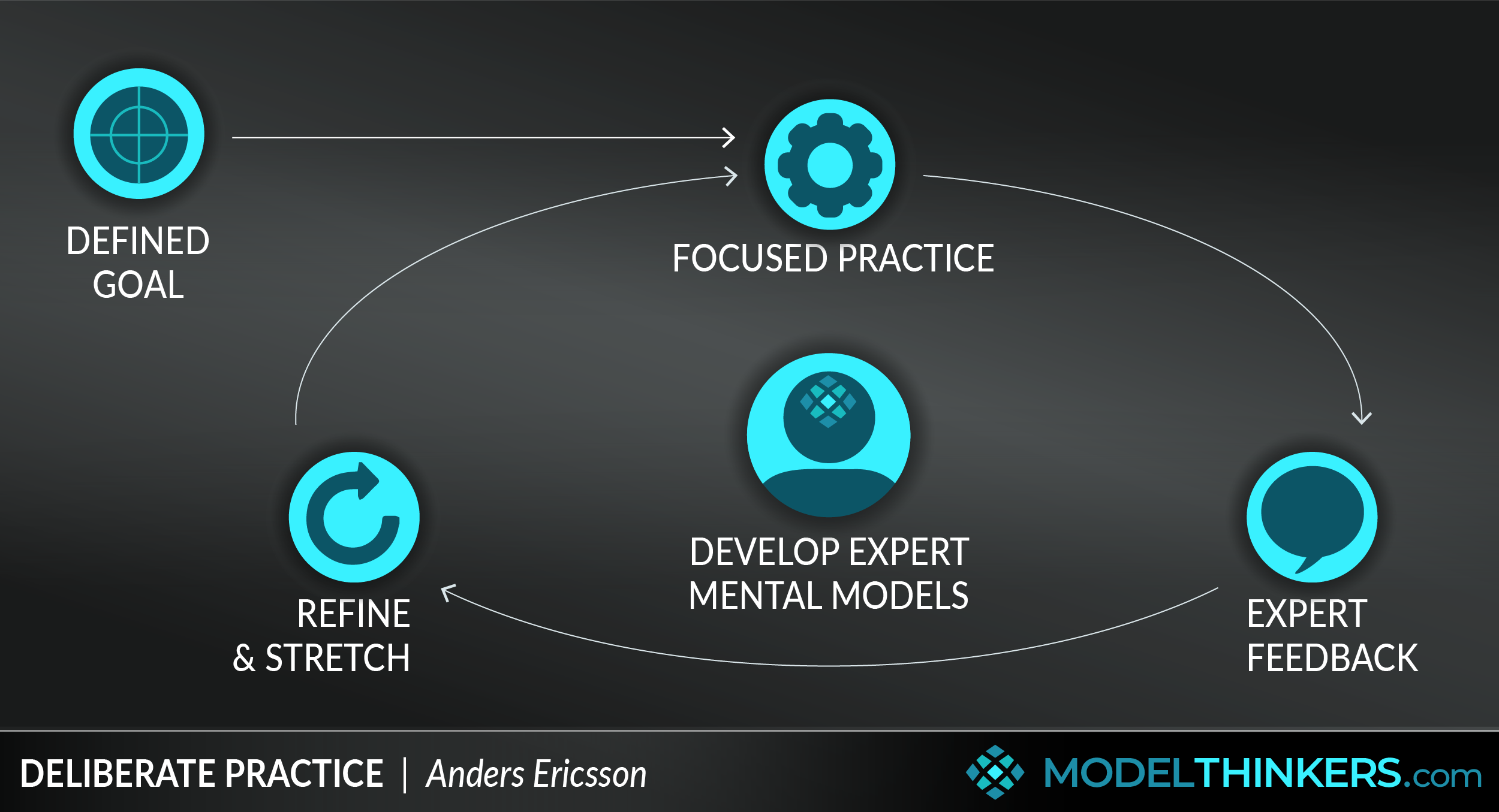

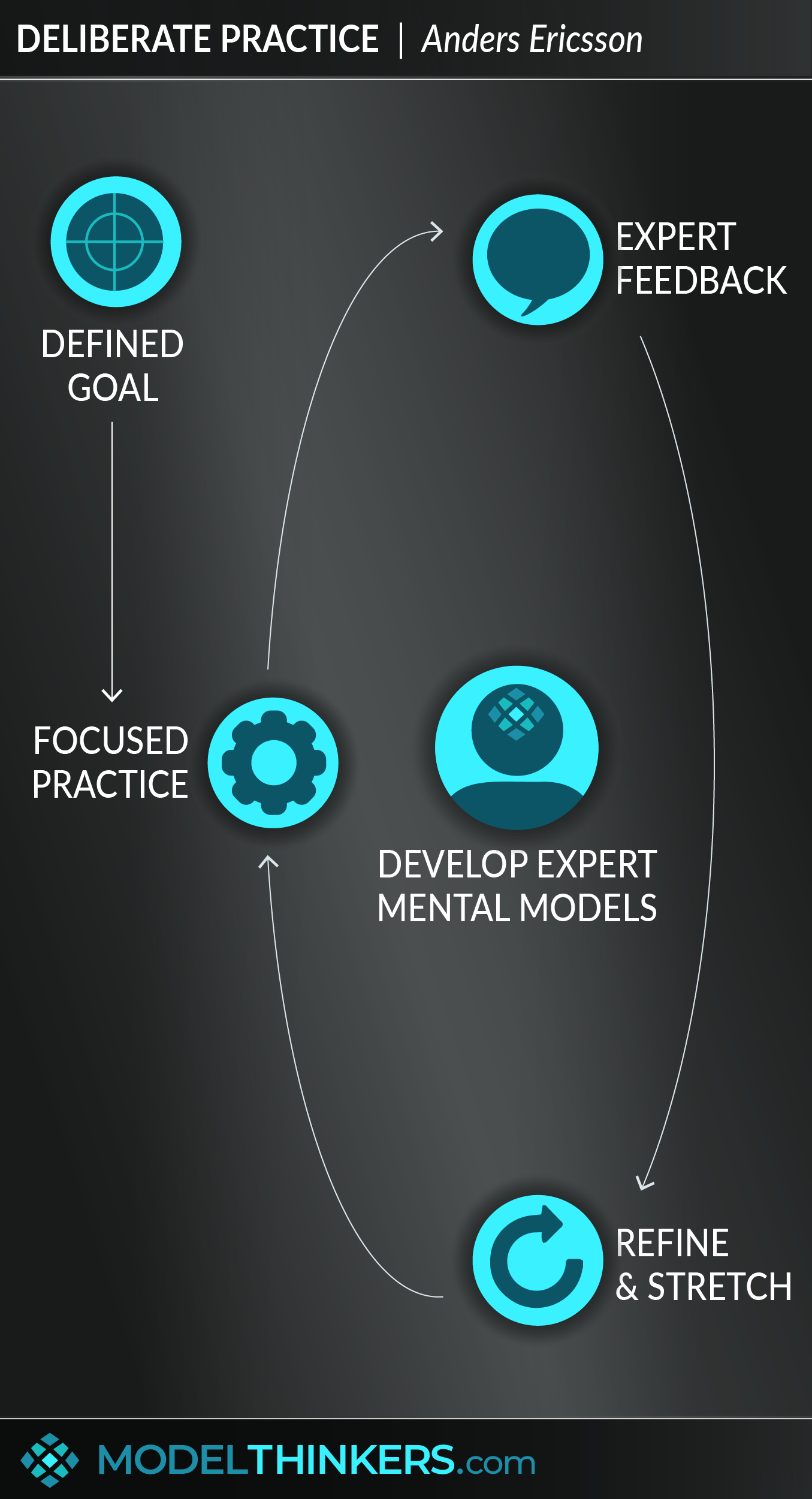

Deliberate Practice involves choosing a specific goal; breaking that down into key aspects of focus; investing regular, effortful and targeted periods practice; gaining expert feedback; and using that to correct, stretch and refocus on areas that need improvement.

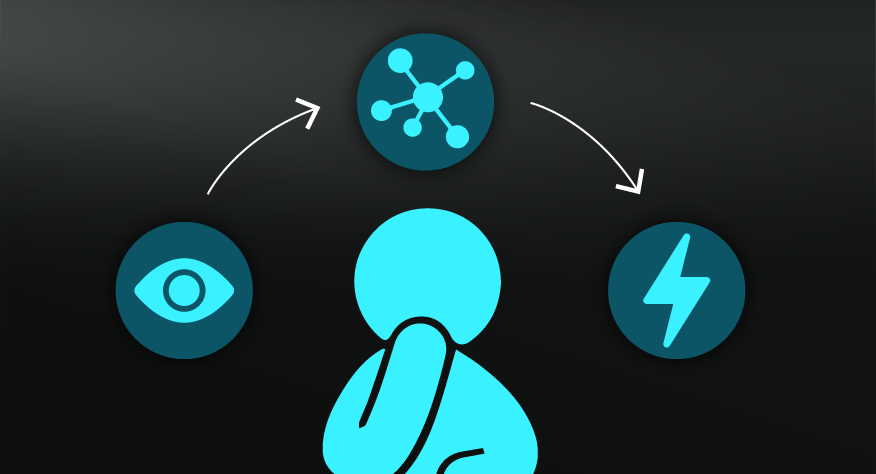

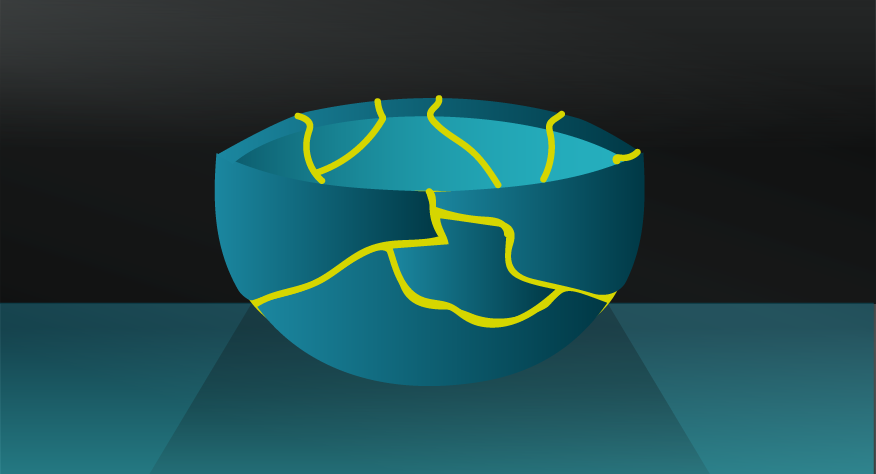

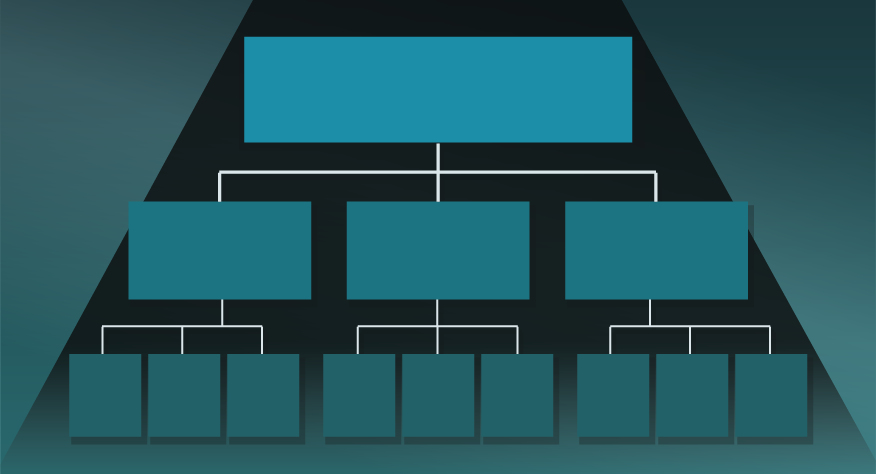

DEVELOPING EXPERT MENTAL MODELS

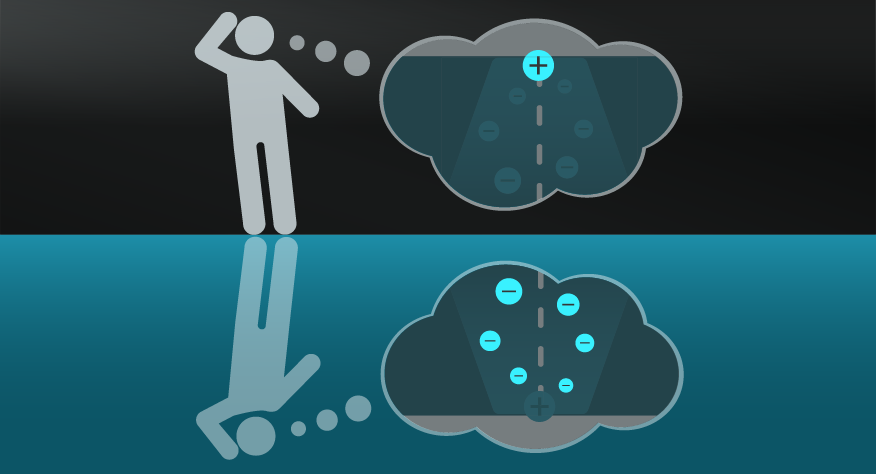

Done repeatedly, this process will help establish expert Mental Models in that domain.

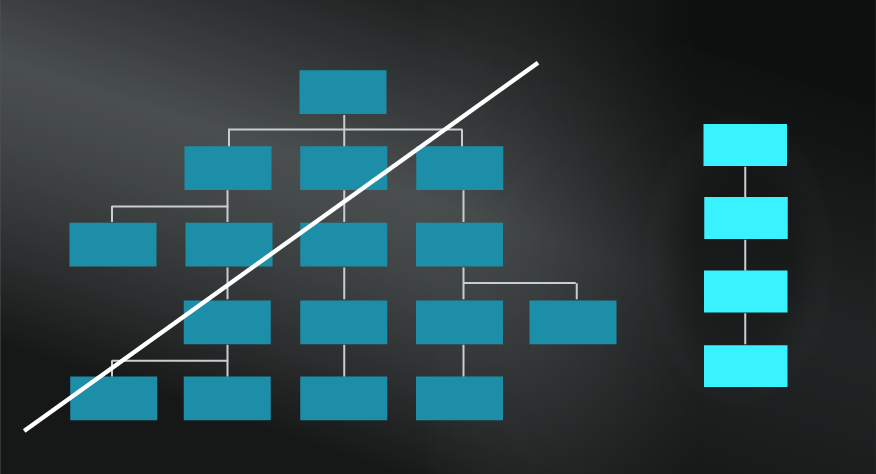

Anders Ericsson, the pioneer researcher of Deliberate Practice described these Mental Models, or ‘mental representations’, as “pre-existing patterns of information — facts, images, rules relationships, and so on — that are held in long-term memory and that can be used to respond quickly and effectively in certain types of situations.

'The thing that all mental representations have in common is that they make it possible to process large amounts of information quickly, despite the limitations of short term memory.”

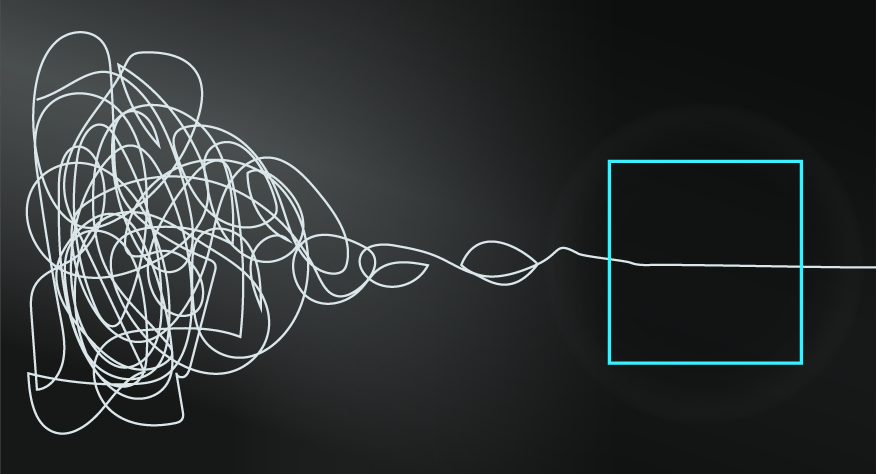

NOT JUST TURNING UP.

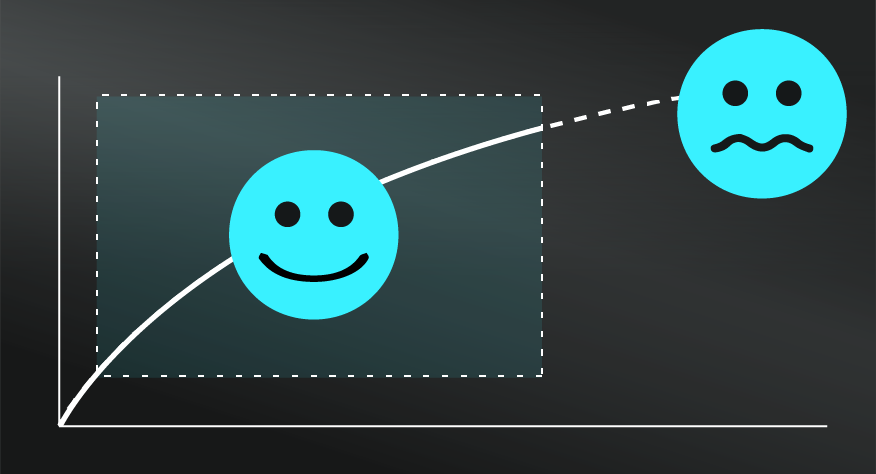

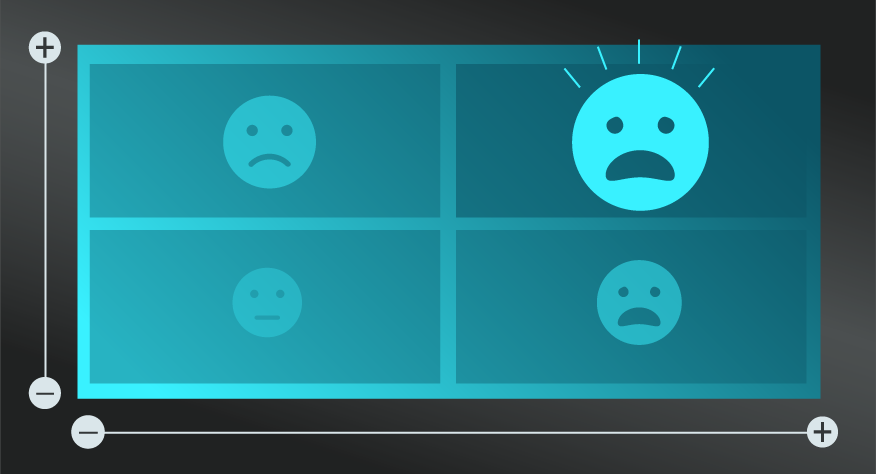

For further clarity, let’s consider what Deliberate Practice is not. It is not ‘just turning up and going through the motions’ — so repetitive practice alone won’t cut it. Nor is it focused practice without Feedback Loops – that is input about ‘what good looks like’. And finally, it’s not practice with feedback, without reflection to update and refocus. The process of reflecting to improve mental models can also be compared to Double Loop Learning.

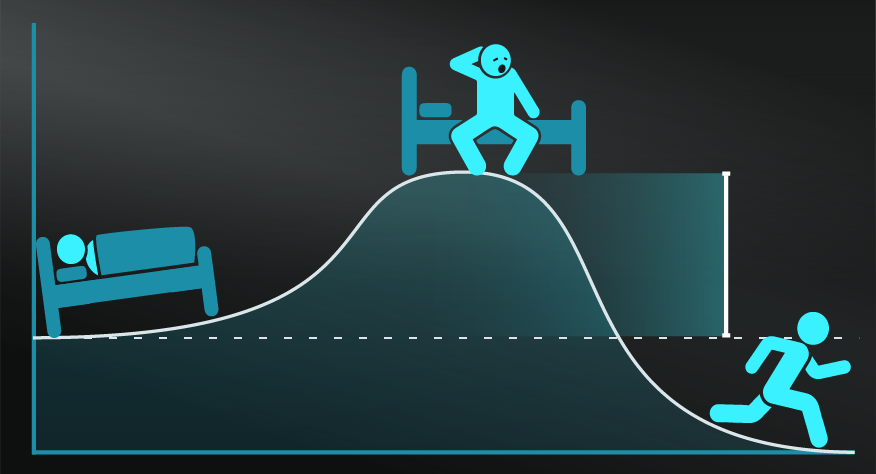

Indeed, Deliberate Practice is effortful and will likely leave you cognitively, and perhaps physically drained. It might be viewed as using slow thinking when framed by Kahneman's model of Thinking Fast and Slow.

BORAD RELEVANCE TODAY.

Ericsson research suggests that these techniques can be applied to diverse fields from the arts, medicine, sports, martial arts, and a range of professions. For best results, consider combining with spacing, as described in the Spaced Retrieval model.

While there are critiques of his work (see Limitations below), I’ve found Ericsson's model to be extremely powerful in developing a range of complex skills, including soft skills. In that sense, it's an invaluable companion for anyone interested in developing as a T-Shaped Person.

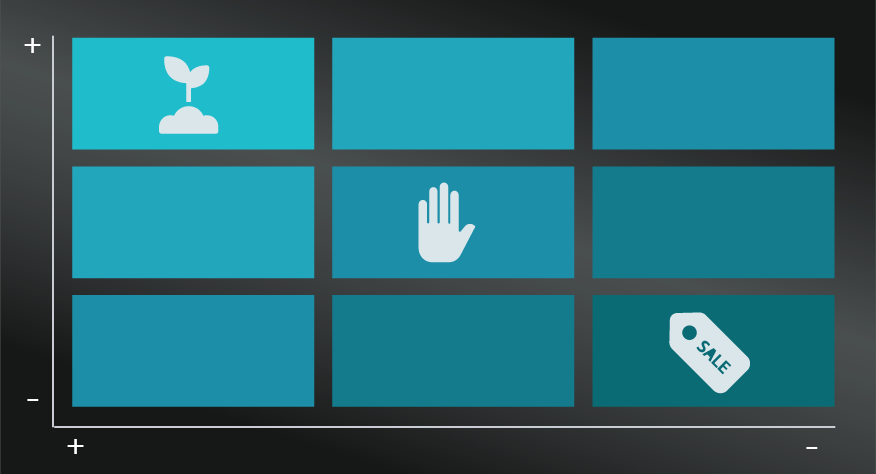

- Choose an area of development and break it down.

Select an area of expertise that you wish to develop and break down the main skills. Choose one to focus on in your first round of practice. For example, if you wanted to be a better public speaker, you might consider sub-skills of structuring a narrative; reading an audience; starting with a hook; using body language; maintaining energy; speaking from notes; and speaking clearly.

- Commit to regular, deliberate practice.

Find a way to practice your chosen skill in regular, spaced sessions. There are some links to spaced retrieval here, as consistent, spaced sessions have been shown to be effective.

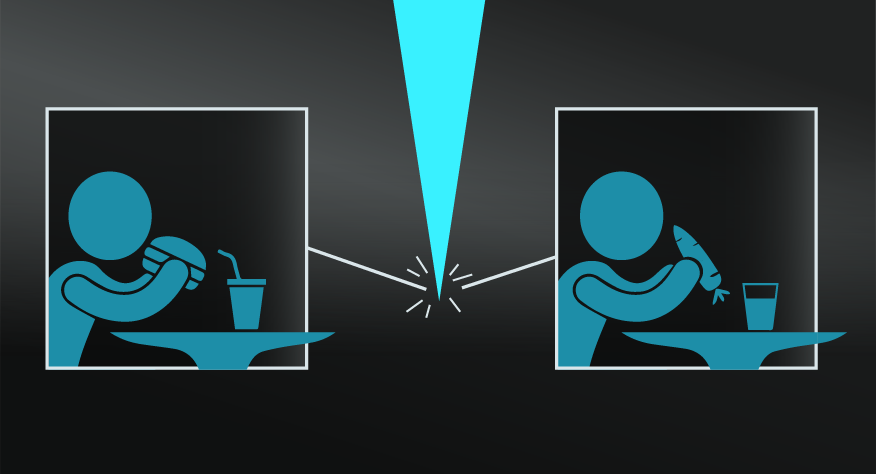

- Develop feedback loops.

You need to know what good looks like and have your practice critiqued to uncover your remaining gaps and areas of improvement. This can be done with data points or expert feedback to help accelerate the formation of expert mental models.

- Update, refocus and stretch.

Use the feedback and information on your gaps to aggressively target them with new practice routines. Consider how to stretch yourself, pushing yourself beyond the normal routine as you repeat the cycle.

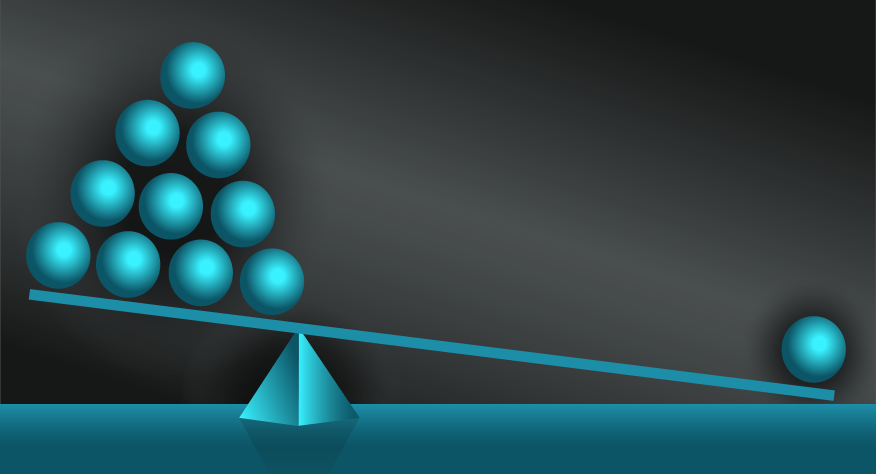

Ericsson has had his share of recognition but also a generous amount of critiques. Some researchers dispute that deliberate practice can impact equally across all types of skills - pointing to this study which seemed to show a greater impact in games and music over education and professional development, which are believed to have less ‘stable structures’ and be more unpredictable.

Others critique Ericsson for solely focusing on deliberate practice over genes, biology and ‘natural talent’. While many would agree that deliberate practise can play a crucial role in developing talent, Ericsson tended to dismiss biology as a factor at all. This critique is explored in this New Yorker article.

Remembering numbers.

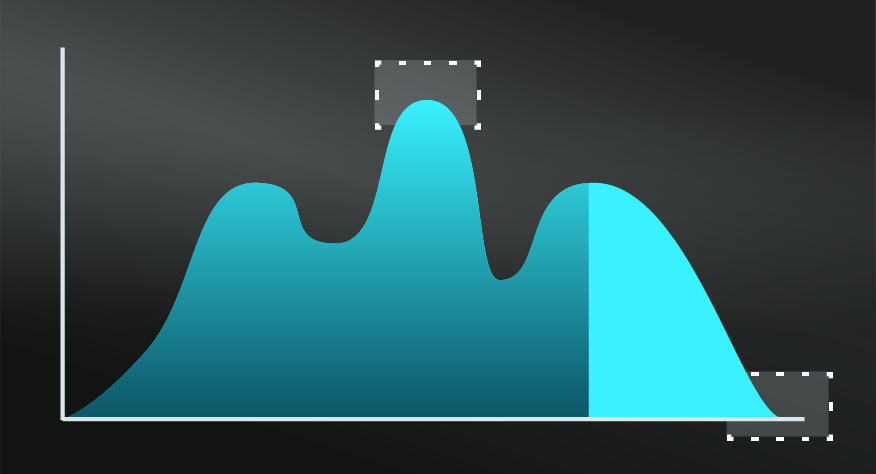

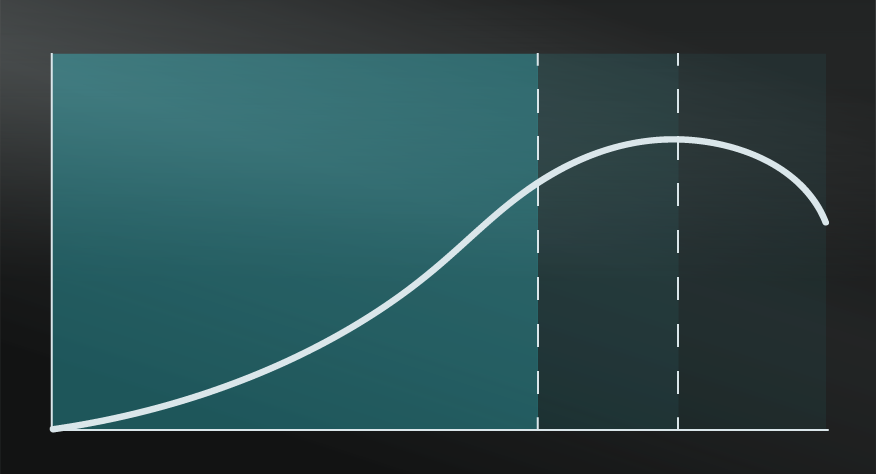

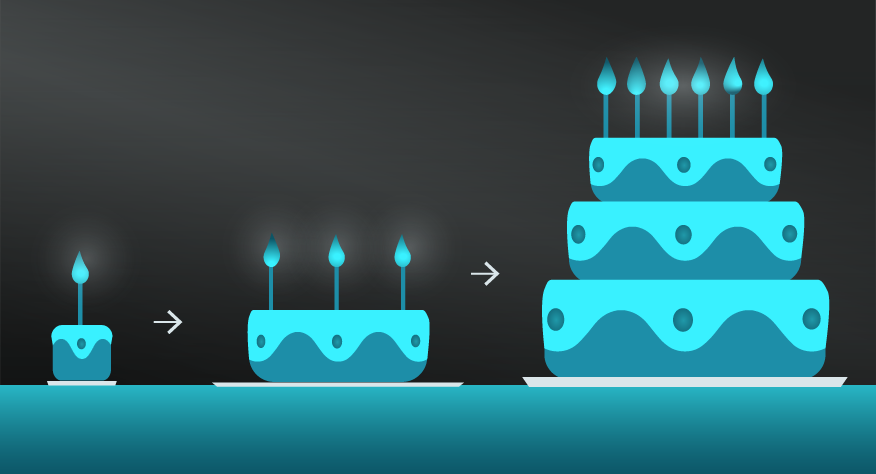

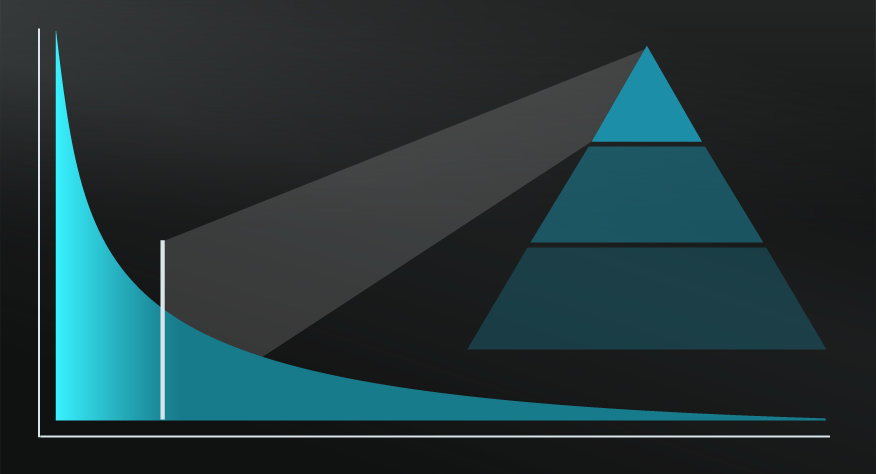

One of the case studies covered in depth by Ericsson was an experiment he ran with Steve, one of his students. Steve was charged with memorising random five-digit numbers. If he got it correct, Ericsson would increase the string to 6, 7 and so on. When Steve made a mistake, Ericsson would reduce the string by 2 digits and keep going — so he always worked on the edge of his comfort zone.

Steve experienced periods of plateaus — first at 7 to 8 digits before persistence saw breakthroughs. Following this cycle, he eventually reached 82. Most interestingly, the next student to go through the same process was coached by Steve. The second student was able to fast track their progress by learning from Steve’s expert mental models and techniques.

Benjamin Franklin and writing.

While he didn’t call it Deliberate Practice, based on his own descriptions it seems as though Ben Franklin used a form of deliberate practice to develop his writing skills. As a teenager, he chose examples of strong writing from the Spectator. He captured notes about an article, set it aside for a few days, then came back and tried to write an article from his notes.

He explained: “Then I compared my Spectator with the original, discovered some of my faults, and corrected them.”

Deliberate practice is an important model in developing complex skills and relates to spaced retrieval.

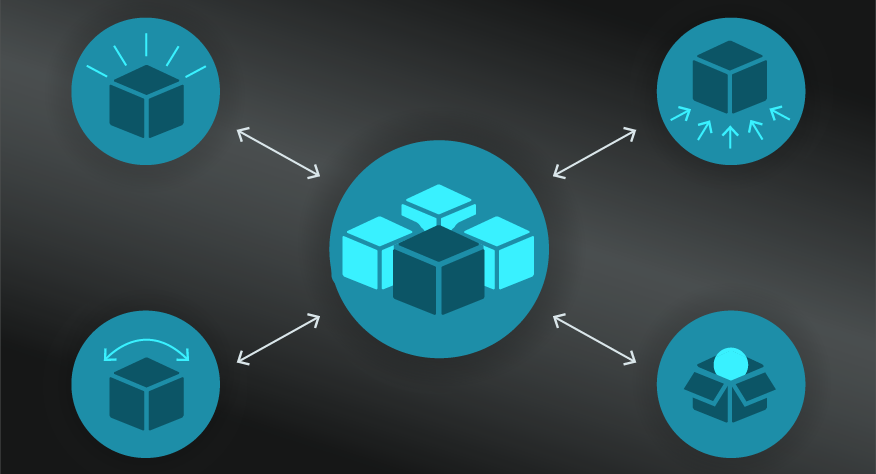

Use the following examples of connected and complementary models to weave deliberate practice into your broader latticework of mental models. Alternatively, discover your own connections by exploring the category list above.

Connected models:

- Mental models: the approach includes ‘expert mental models’ through deliberate practice.

- Feedback loops: the cycle of practice and feedback supports continuous improvement.

- Spaced retrieval: deliberate practice is best implemented via spaced sessions.

Complementary models:

- T-shaped person: in identifying key skills to develop.

- The habit loop: when not pushing your comfort zone, behaviour can become passive and habitual.

- Domino effect and compounding: starting with small gains by targeting defined skills and building through marginal gains.

Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson was a key researcher and advocate for Deliberate Practice. His excellent book Peak, in part, clarified his position after Malcolm Gladwell used his research to promote the 10,000 hours to mastery concept.

For his part, Ericsson argued against the 10,000-hour approach, pointing out that the key factor was conscious deliberate practice over simply turning up.

My Notes

My Notes

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”