0 saved

0 saved

31.2K views

31.2K views

Writers as diverse as Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare and even J.K Rowling have demonstrated the power of cliffhangers in fiction, but why limit this device to stories? Apply the Zeigarnik Effect to improve your learning, productivity, relationships, and even your mental health.

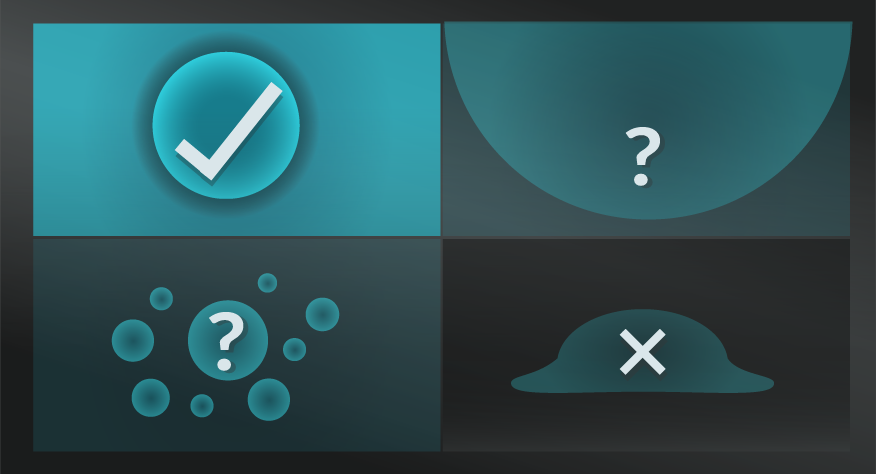

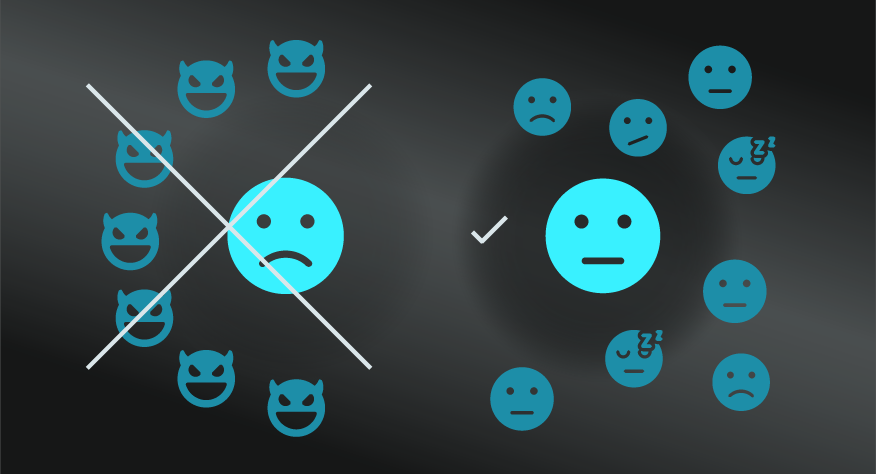

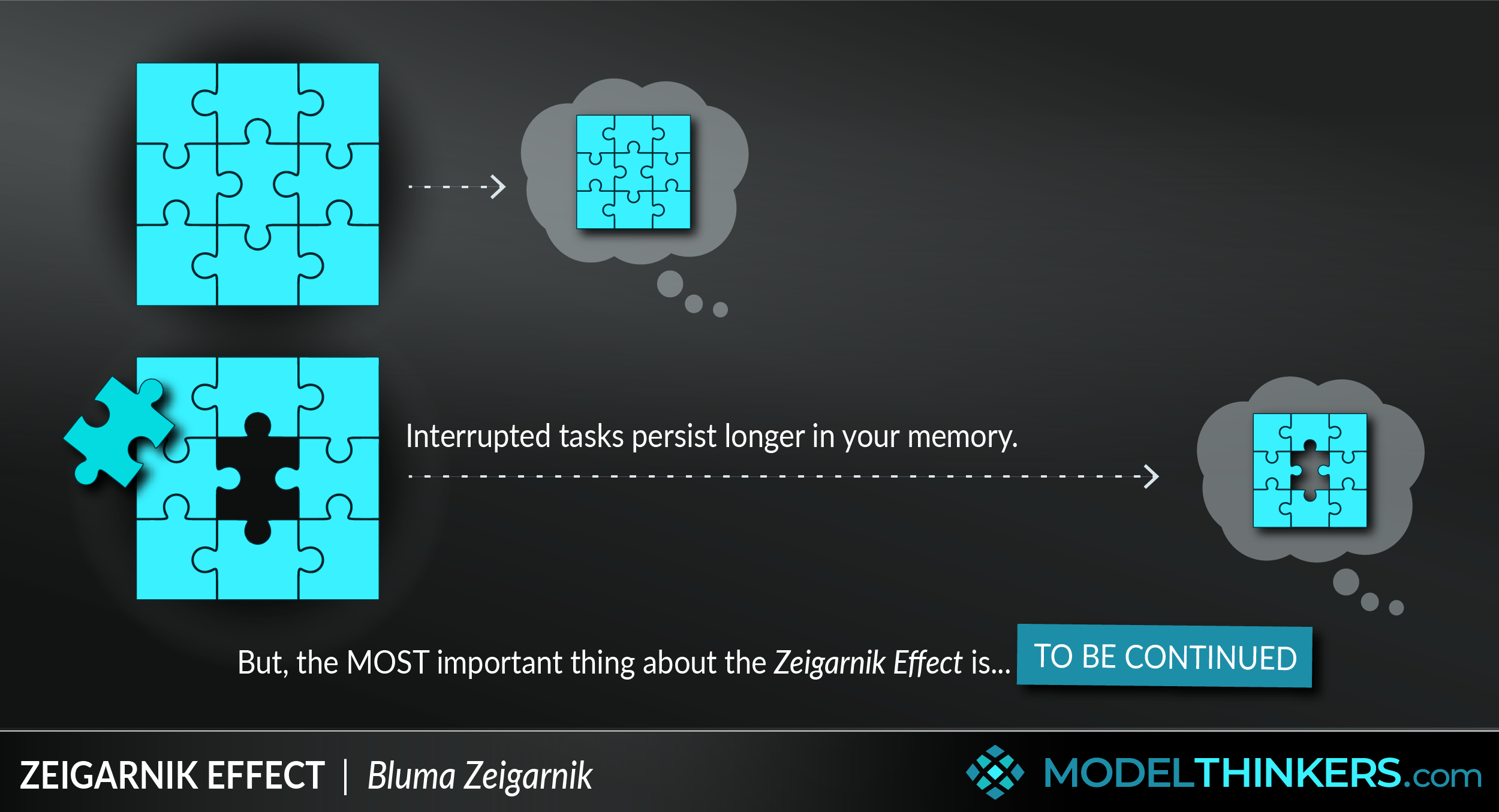

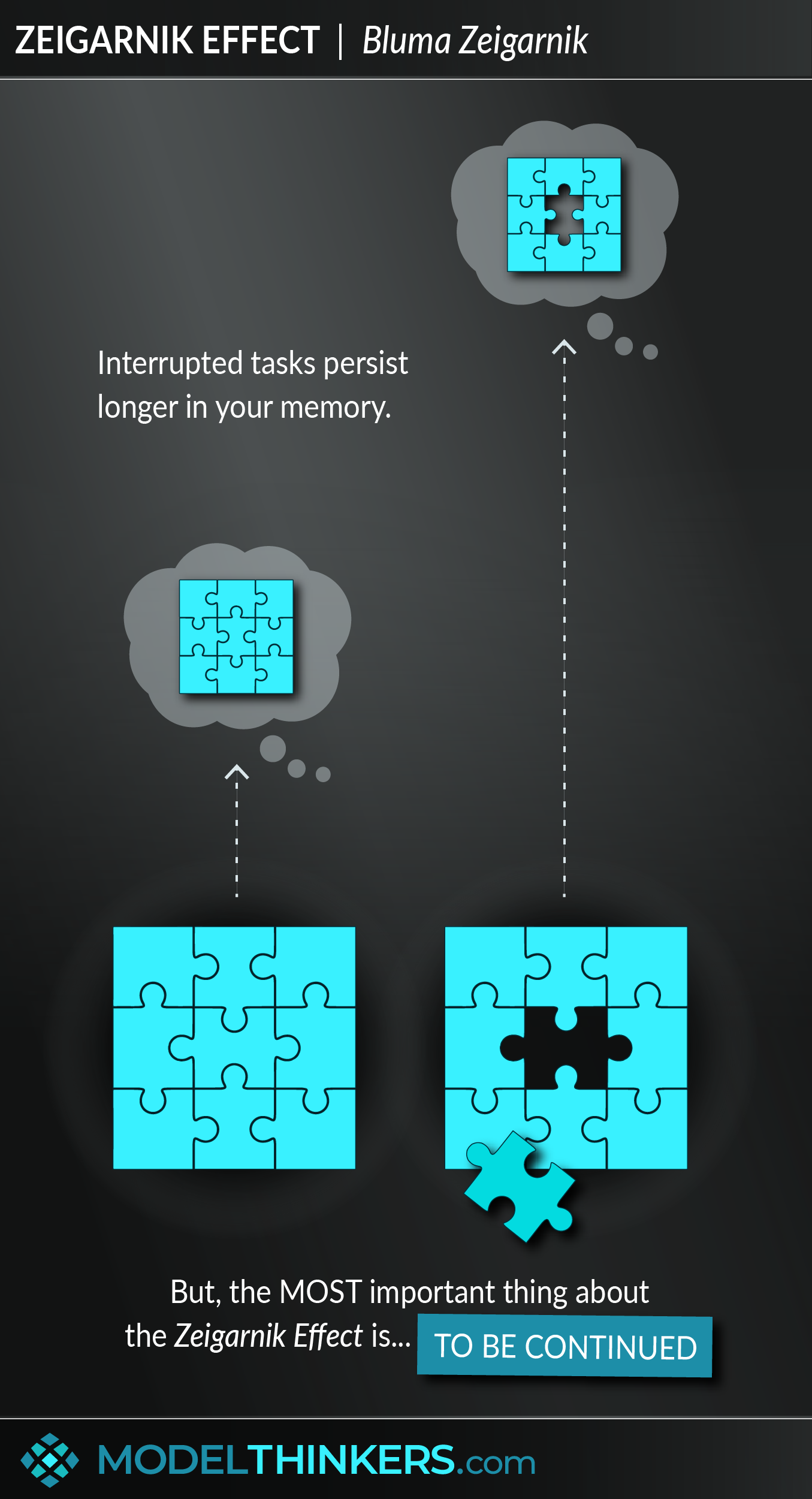

The Zeigarnik Effect describes your tendency to remember interrupted or incomplete tasks more than completed ones.

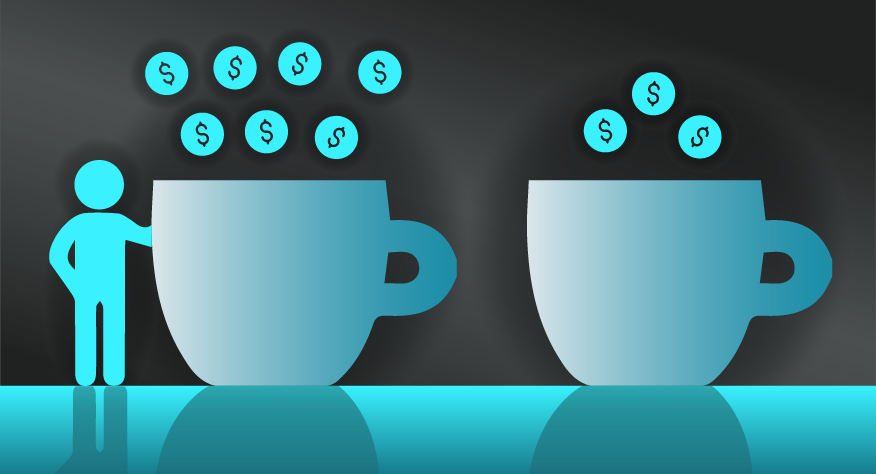

A TRIP TO A CAFE.

This model can be traced back to the 1920s when Bluma Zeigarnik, a Soviet psychologist, was sitting in an Austrian Cafe. Zeigarnik noticed that the waiters in the cafe consistently memorised complex food orders from patrons but, as soon as the order was delivered, the waiters seemed to forget the order. Zeigarnik’s resulting hypothesis was that, because our brains are so goal-focused, unfinished tasks would remain in our memory longer than finished ones.

In a sense, such unfinished tasks create a ‘cognitive tension’ in our minds that demand ongoing focus and thought. See the Origins section below for how she researched and tested this hypothesis.

GOALS VS PLANS.

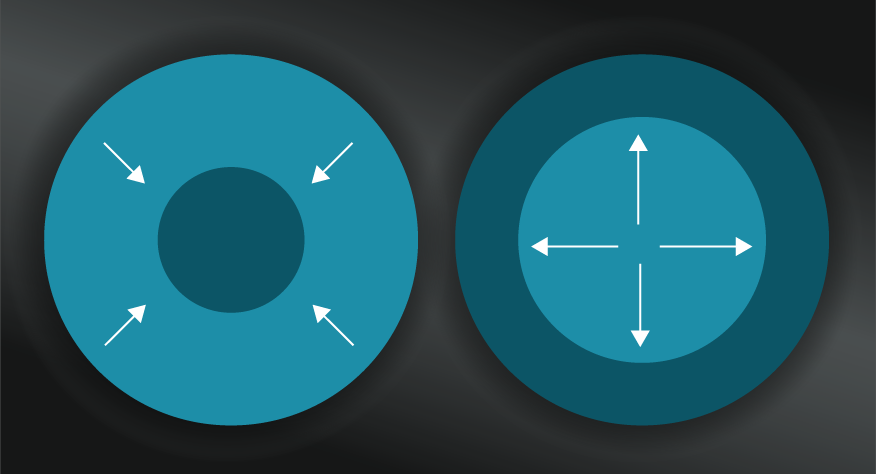

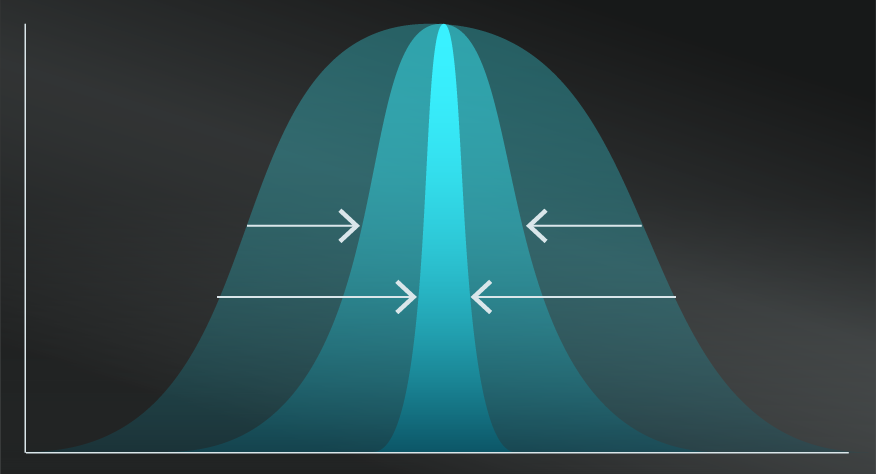

While Zeigarnik’s original thesis focused on incomplete goals, recent research has discovered that making a plan to complete an unfinished goal will reduce the Zeigarnik Effect. In other words, simply making a plan or scheduling an unfinished task might be enough to create a sense of ‘mental completion’, allowing you to forget the unfinished task.

View Limitations below for other complicating factors with how this model plays out, including motivation and perceived difficulty of tasks.

APPLICATIONS.

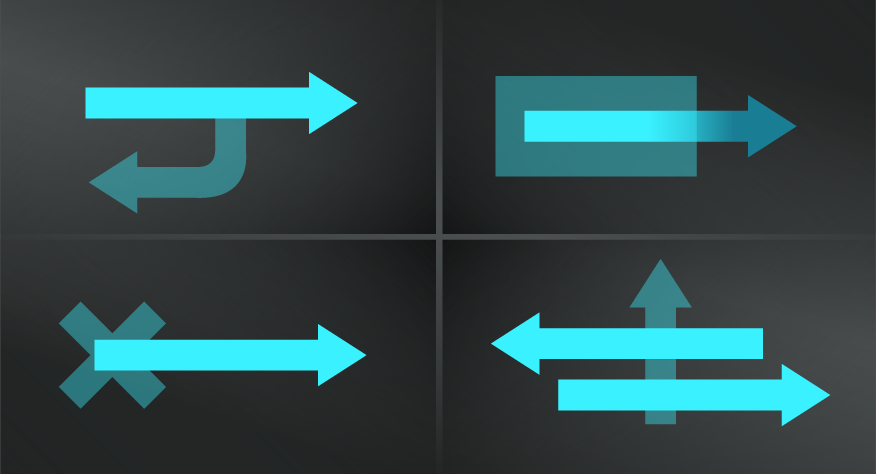

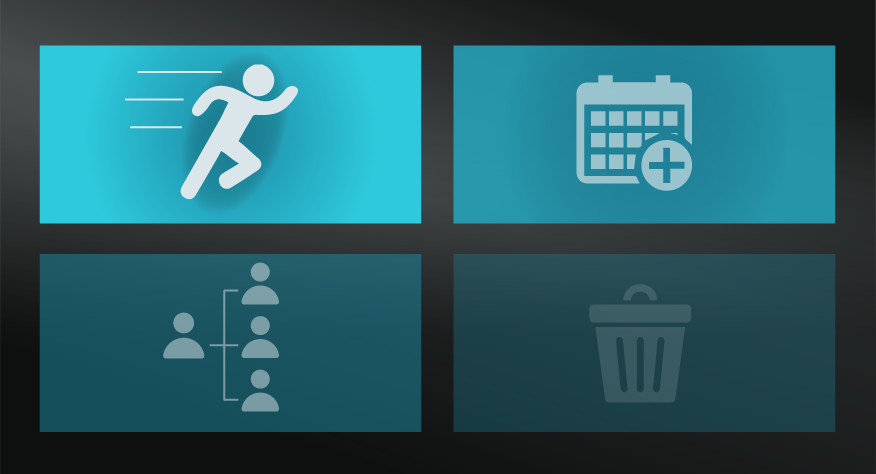

There are many potential applications of this mental model, including:

-

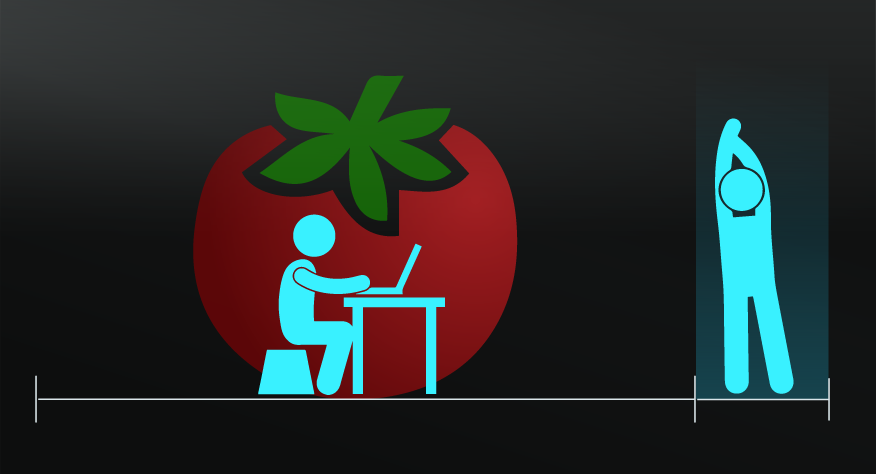

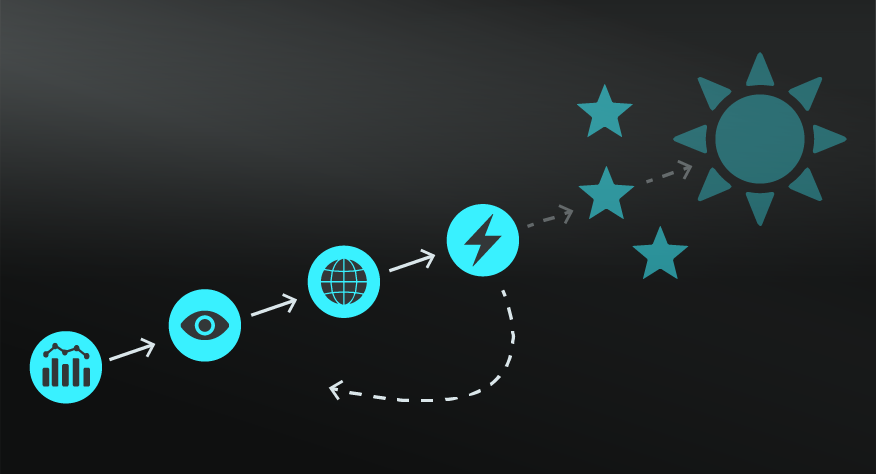

Learning. Use the Zeigarnik Effect to interrupt your learning and create an ‘unfinished state’ with important topics to better embed them into memory.

-

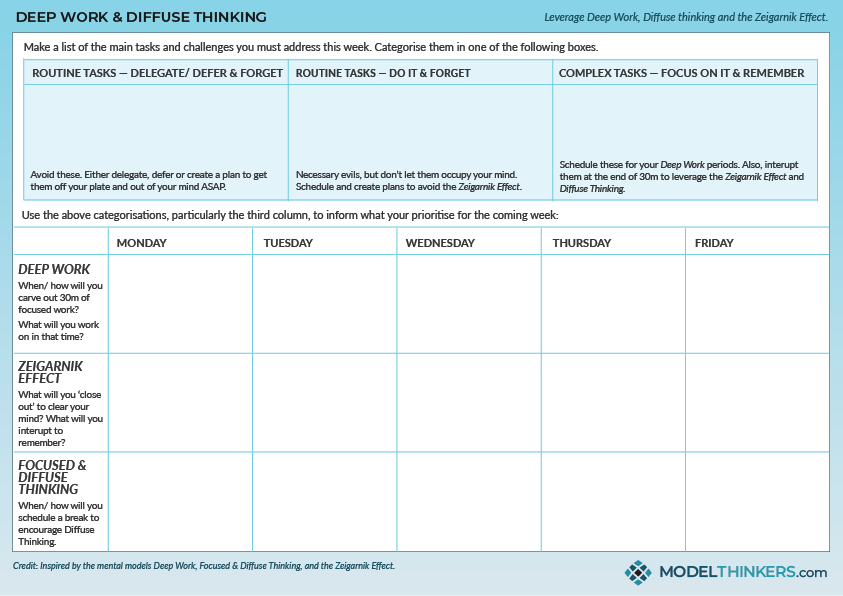

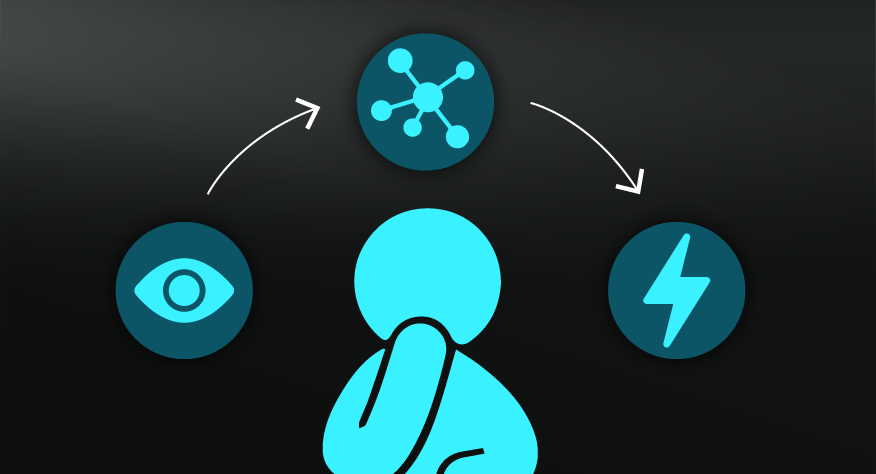

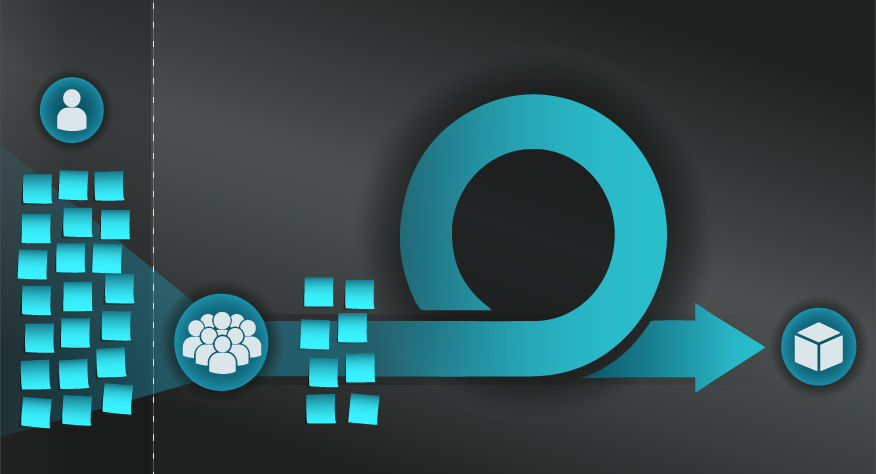

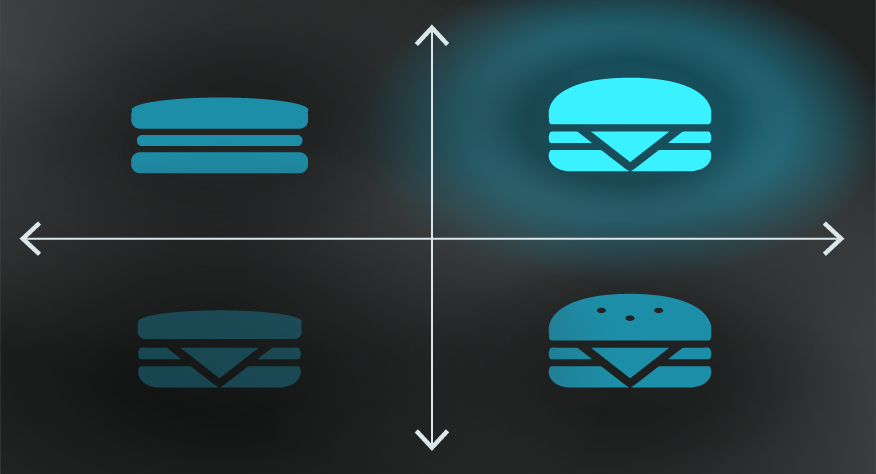

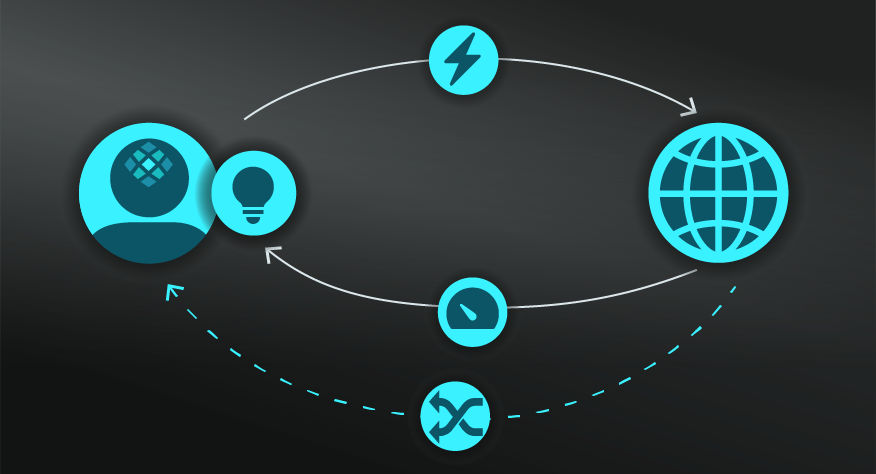

Innovation. Combine this model with Focused and Diffuse Thinking to consciously seed ‘incomplete’ problems and key questions into your subconscious mind for more diffuse and creative problem-solving. See the canvas at the bottom of this page for more.

-

Task motivation. Strategically interrupt important work at key moments to ensure that it remains front of mind and that you are driven to return and complete it as a result.

-

Mental health. Apply the mental model in reverse, working to close 'open loops' and achieve a sense of ‘closure’ that will support you to be more present and reduce overwhelm and anxiety.

-

Marketing and communication. Use cliffhanger styled storytelling techniques to ‘hook’ an audience and keep them engaged in your narrative. This might include posing a question, a problem or a surprising idea that you answer and address later.

-

UX. Create gradual goals and feedback for users to give them a sense of progress and encourage them to strive for completion, e.g. ‘Your profile is 40% complete, why not finish it now?’

-

Relationships. Remember that rule about not going to bed angry with one another? According to the Zeigarnik Effect, it’s a thing. You don’t even have to resolve everything, just identify a plan or a time where you can address issues and points of conflict.

IN YOUR LATTICEWORK.

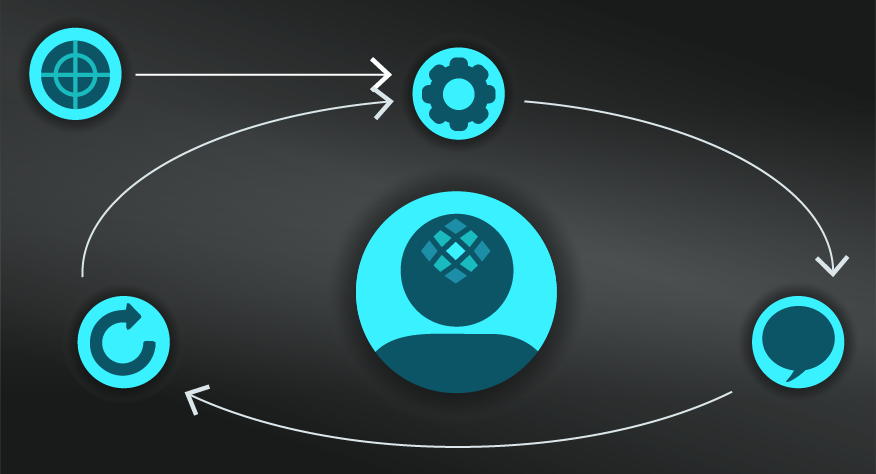

We’ve already mentioned how the Zeigarnik Effect is a wonderful companion model with Focused and Diffuse Thinking and Deep Work for innovation and problem-solving. In fact, see the canvas at the bottom of this page for a practical guide of combining these three models.

Beyond that, in a learning context, consider combining it with Spaced Retrieval. Apply your understanding of Activation Energy to this model for improved task completion, for example, consider interrupting work to keep it in your mind and ensure you return to it, even as you’re reducing Activation Energy by providing yourself with an easy re-entry point.

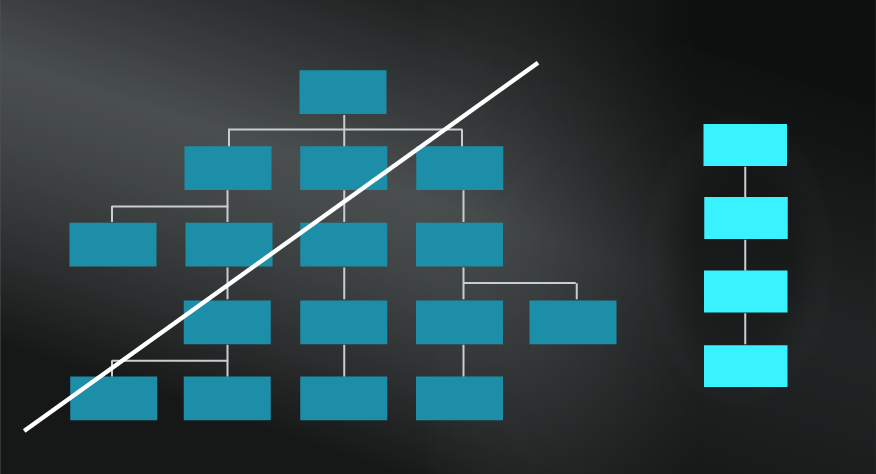

Continuing with the theme of tasks and productivity, use the Zeigarnik Effect to better understand the power of Kanban and other productivity methods that allow you to capture tasks while defining your focus. Compare this to a long list of unsorted tasks that will give you a constant sense of incompletion and potential overwhelm and anxiety as a result.

Finally, consider how you will combine this model with Temporal Landmarks. Such landmarks can help you to develop a mental sense of completion, even if nothing else has changed. So leverage the 'fresh starts' that the morning, beginning of a week, or new year provides.

AND, JUST FOR FUN.

-

Use the canvas.

See the canvas at the bottom of this page for practical help in combining the Zeigarnik Effect with Focused and Diffuse Thinking and Deep Work for a more effective working week.

-

Strategically interrupt to learn and remember.

Consider what information and priorities you want in your memory and interrupt your reading or work accordingly to apply the Zeigarnik Effect.

-

Strategically complete tasks to forget and clear your mind.

Protect your mental health! By the same token as the previous point, consider things you are carrying in your mind that you don’t want there and consider how you might create a sense of completion so you can let go of them cognitively. Remember that you don't necessarily need to actually complete them, you need to seek that 'mental completion' with a plan or sense of closure. And yes, I am talking about that old family clash from your childhood that still gets under your skin!

-

Create plans and schedule tasks.

As noted, recent research has demonstrated that creating plans or scheduling tasks helps to shift unfinished tasks in your mind. This can help you focus, be more present, and reduce anxiety.

-

Make a start on tasks you want to prioritise.

Getting started on a task not only helps you overcome Activation Energy, it also helps you to better fix that task in your mind, maximising your chance of completing it.

-

Use cliffhangers in pitches, communication, stories and marketing.

Hook your audience with something they are interested in and curious about. Then, delay the reveal to maintain interest and engagement.

- Solve complex problems by taking breaks.

Combine the Zeigarnik Effect with Focused and Diffuse Thinking to solve complex problems. Purposefully interrupt your work on a complex challenge to seed that problem in your mind, then go for a walk or just relax to let your subconscious mind, and Diffuse Thinking, to continue to work on it.

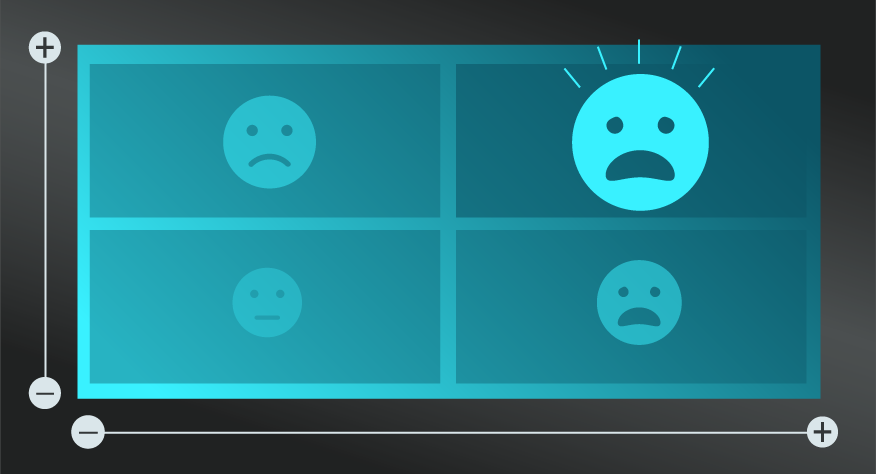

While there has been considerable research supporting the Zeigarnik Effect, there have been studies that have not replicated it and/or point to complicating factors.

Zeigarnik herself pre-empted such criticism, by suggesting that a number of factors would influence the magnitude of the effect, including the timing of the interruption, the motivation of the person, how tired they were, and how difficult they believed the task was.

I’ve already noted the research asserting that planning and scheduling can have a similar effect to completing a task from a cognitive perspective. This research was conducted by Baumeister and Masicampo in 2011 who, for example, found that study participants did worse on a brainstorming task when they were not allowed to finish a warm-up task. However, they were able to improve their brainstorming simply by making a plan to complete the warm-up task.

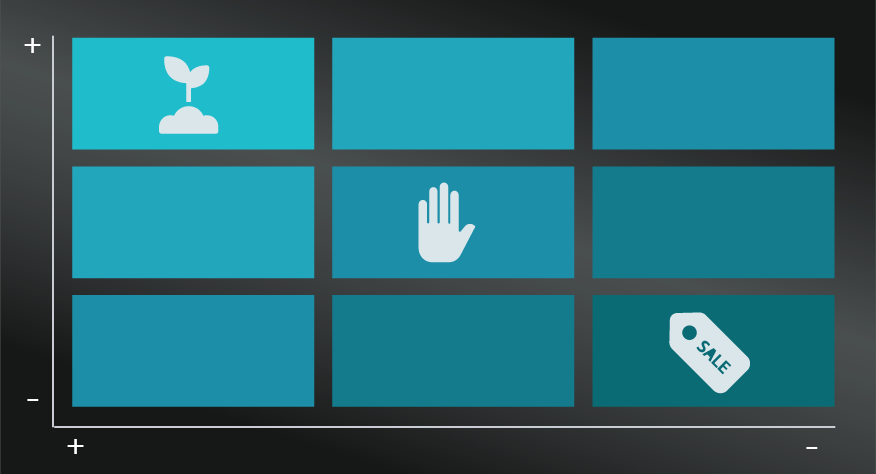

Other research by McGraw and Fiala in 2006, suggested that reward expectancy impacted the Zeigarnik Effect. Specifically, demonstrating that participants promised a reward would less likely to return to a task than those that were not promised a reward.

Kids and learning.

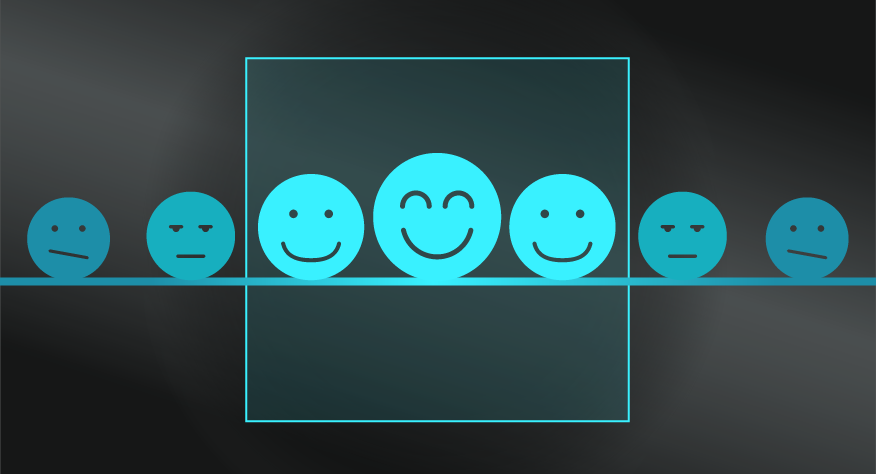

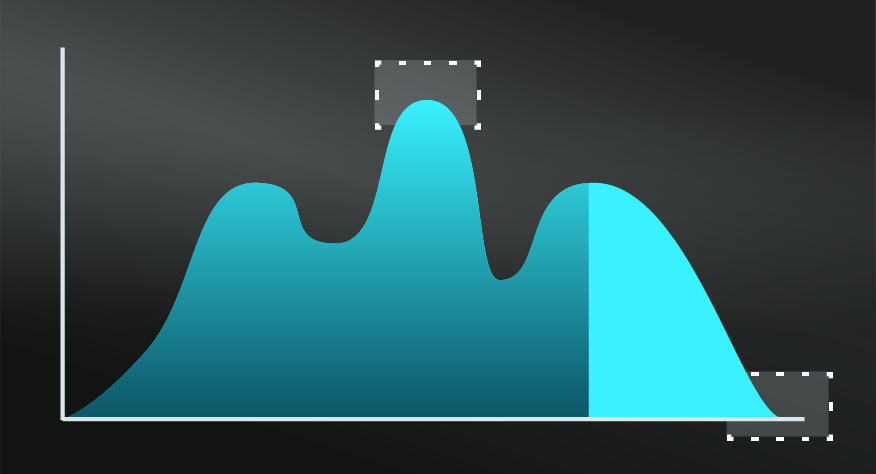

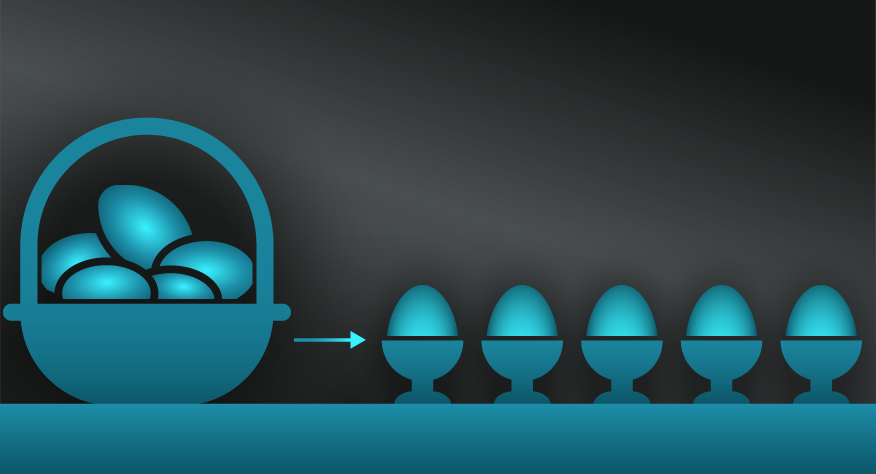

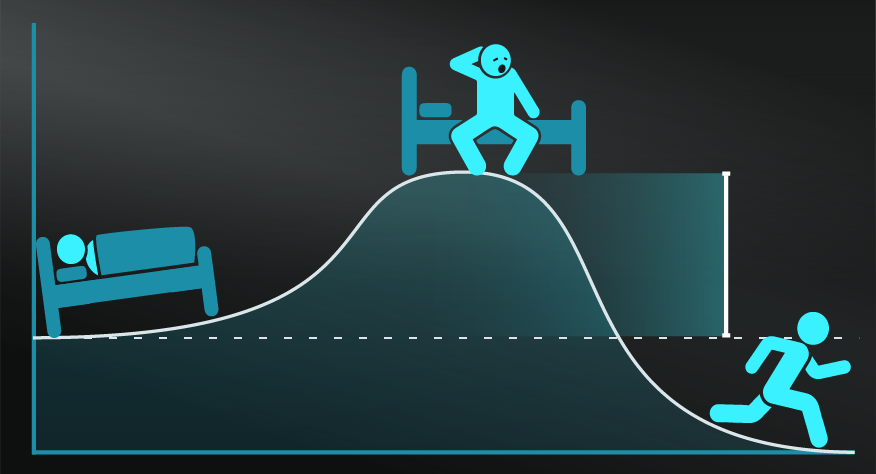

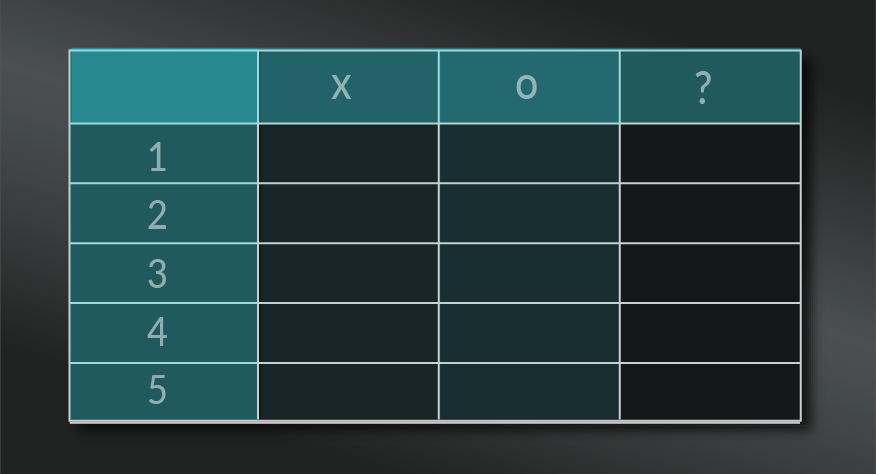

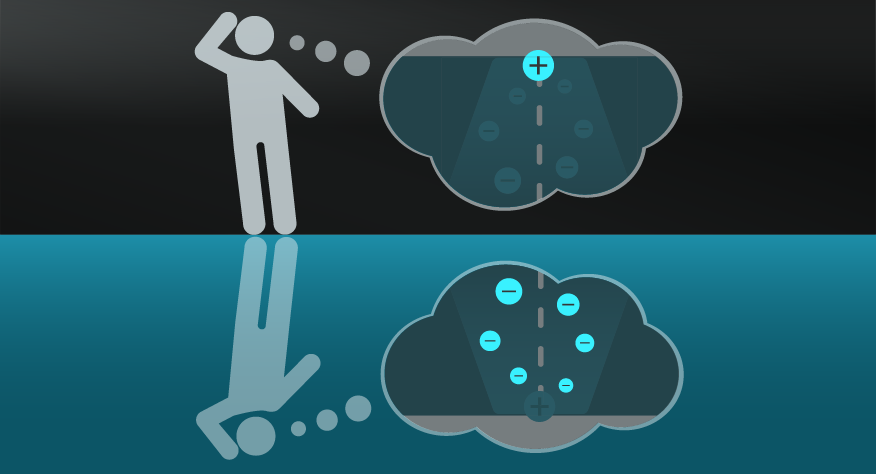

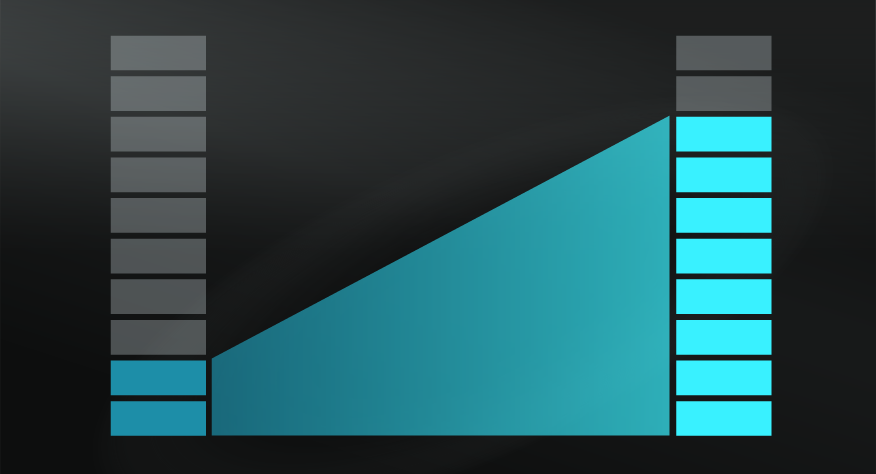

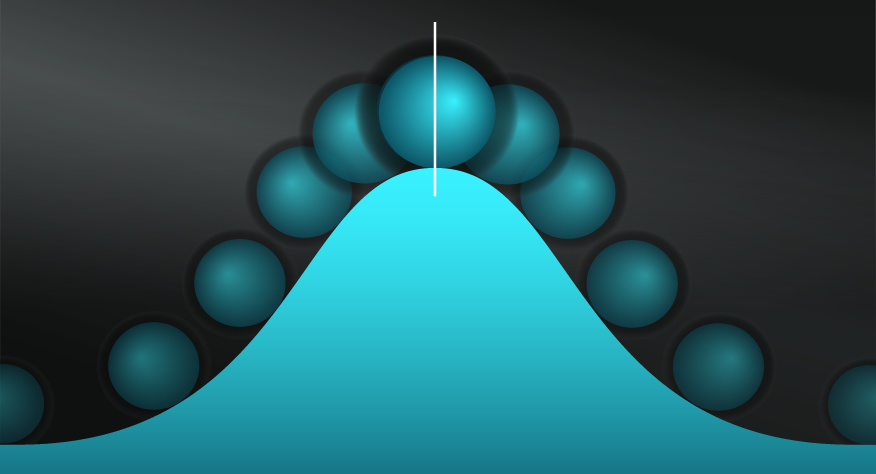

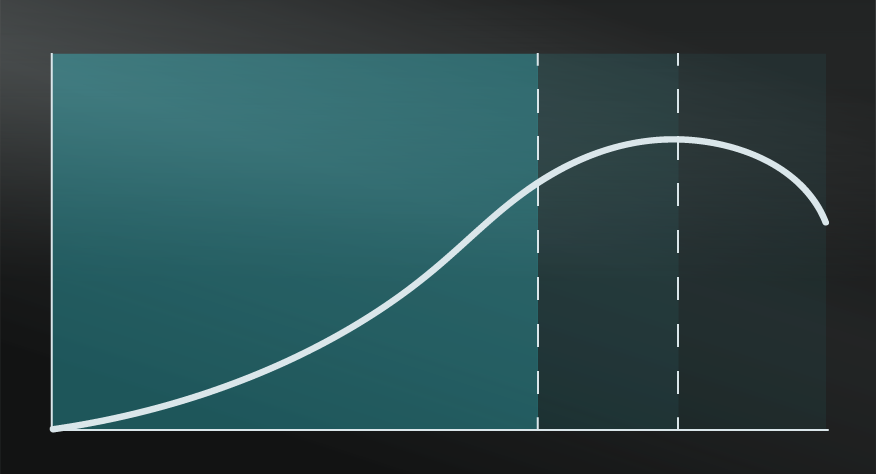

One of the studies that Bluma Zeigarnik ran involved children and learning. She gave 138 children tasks involving puzzles and maths.

-

Group A were allowed to finish without interruption. An hour later 12% of them remembered the tasks.

-

Group B were interrupted. An hour later 80% of them remembered the tasks.

Other experiments saw similar results with adults.

x

The story of Bluma Zeigarnik sitting in an Austrian Cafe in the 1920s to spark her hypothesis has some variations in the retelling. Some describe the waiters forgetting orders after the food was delivered, elsewhere it’s about when the bill was paid. Either way, it does seem that such an experience piqued her curiosity.

It led to a series of experiments, one of which was described in the In Practice section. Many of these experiments involved participants completing simple tasks such as puzzles, a maths problem, or making a clay figure. Her results consistently revealed up to 90% more recall from those who were interrupted in their task completion for both children and adults alike.

Zeigarnik published her results in 1927 in a paper entitled On Finished and Unfinished Tasks.

My Notes

My Notes

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”