0 saved

0 saved

17.9K views

17.9K views

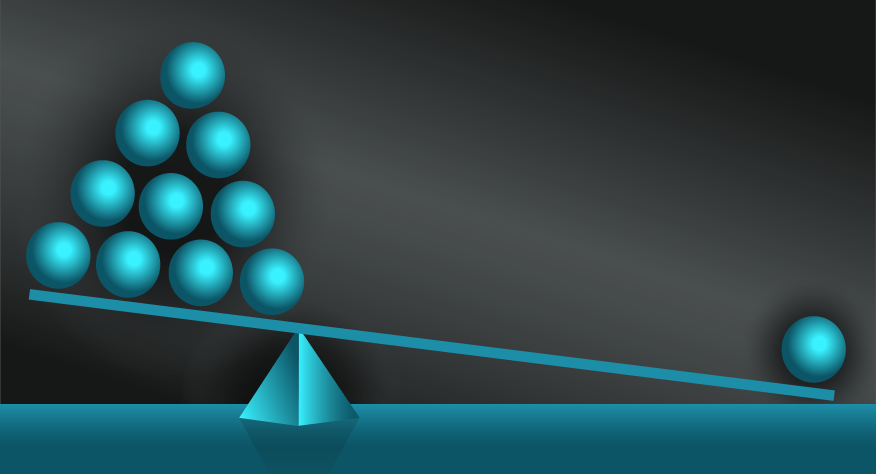

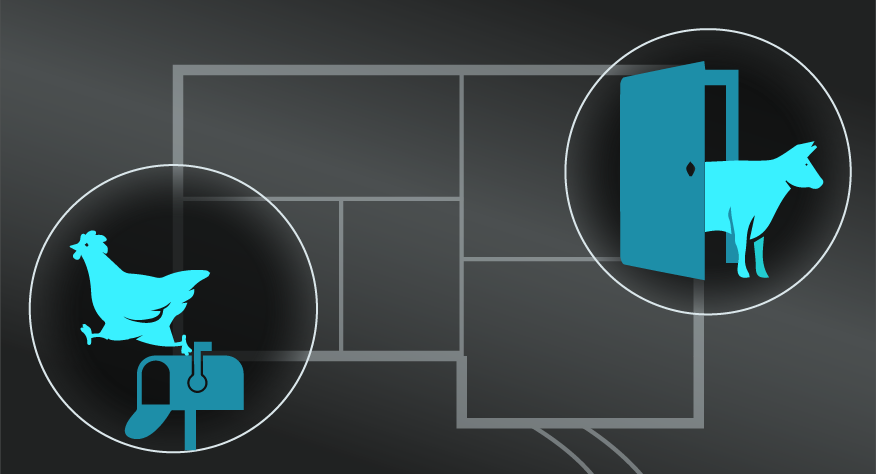

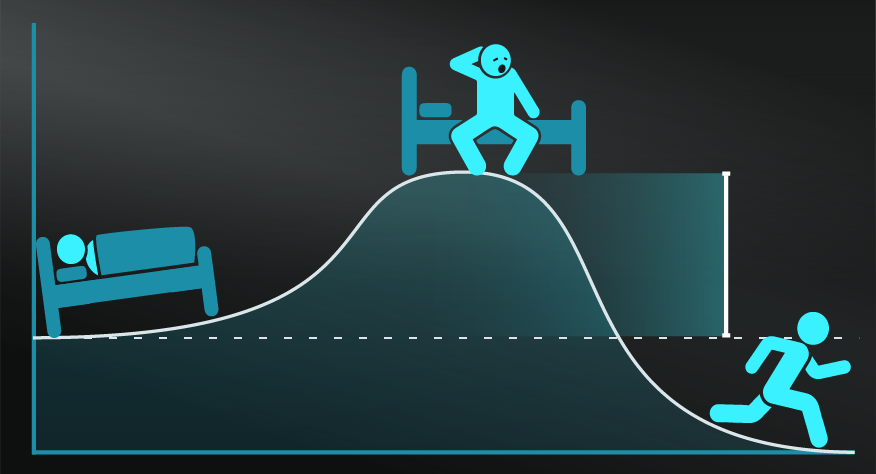

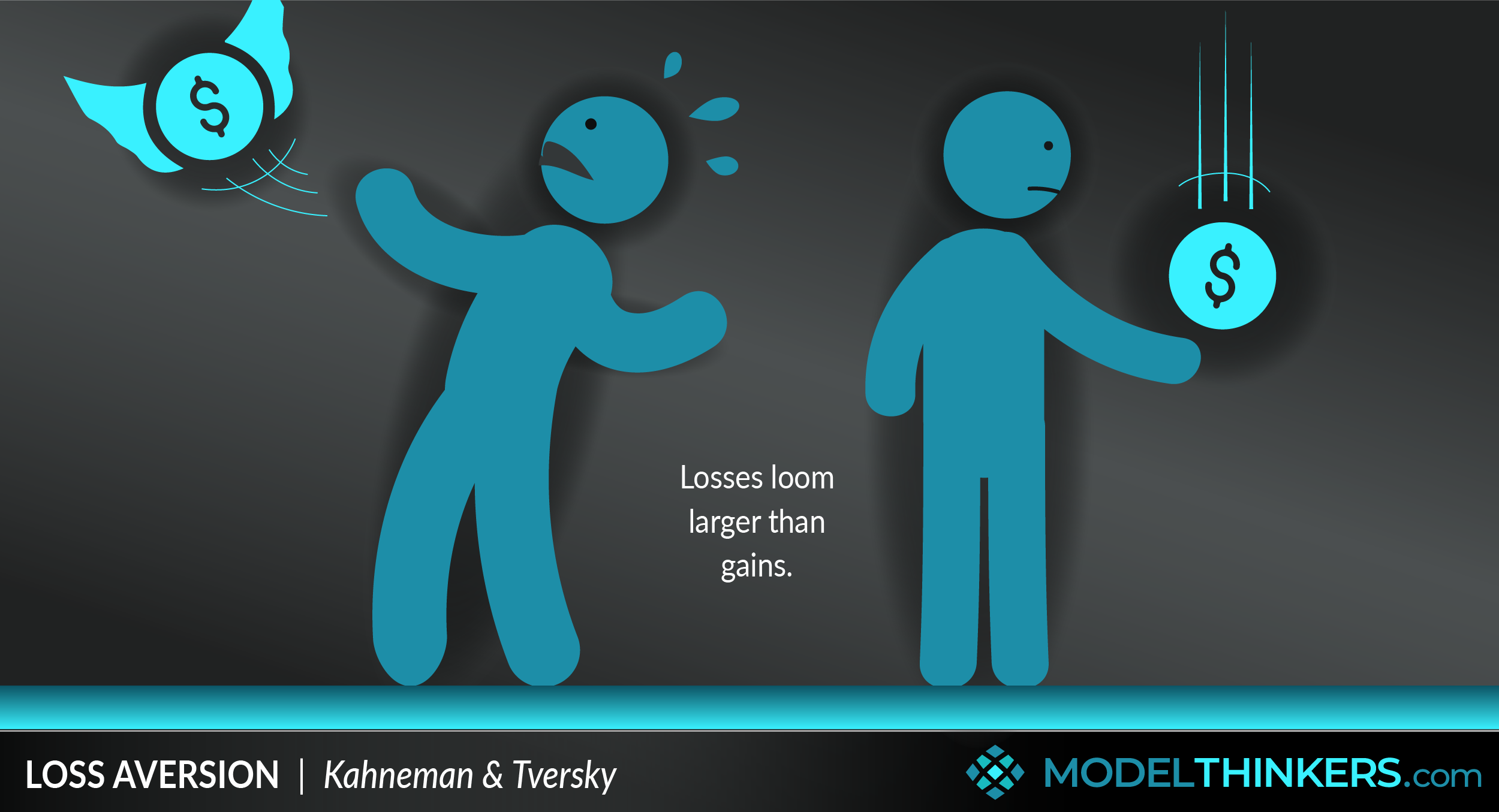

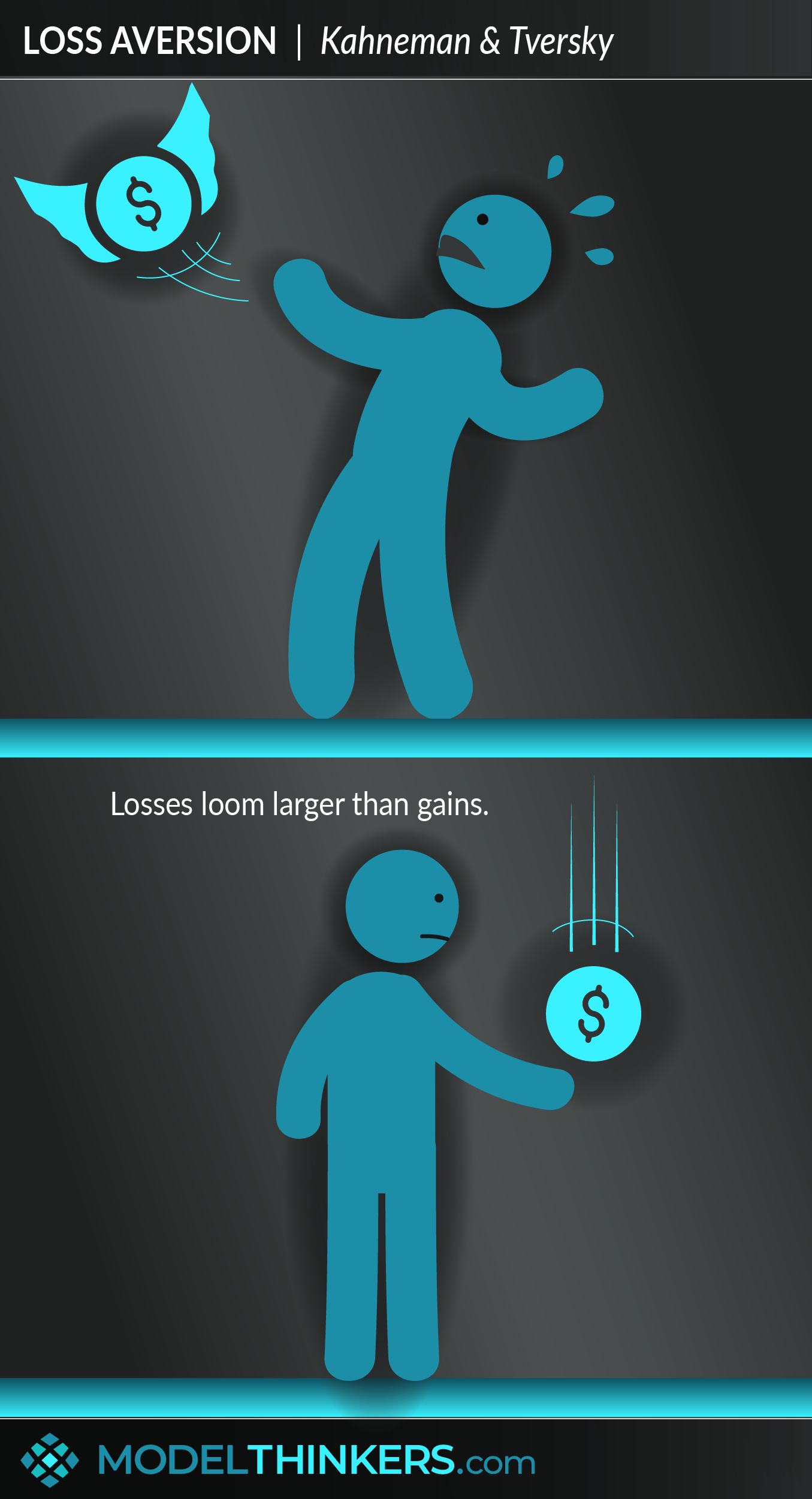

This mental model validates the old expression, ‘a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’. In fact, researchers ...

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

-

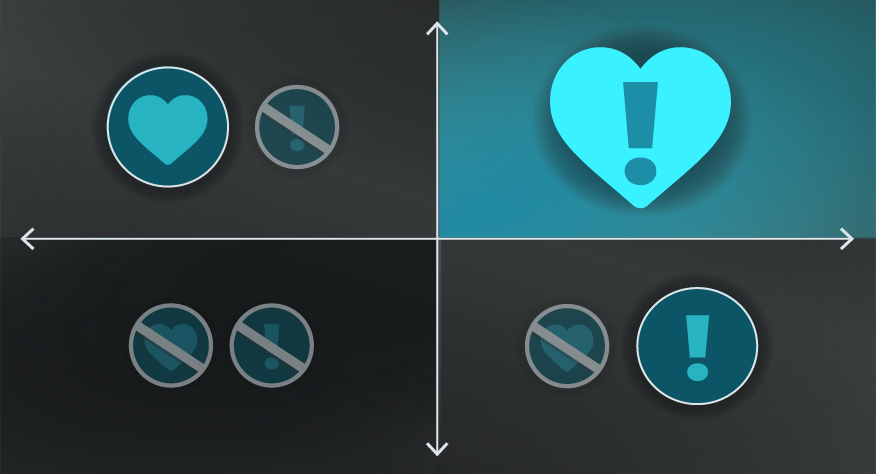

Consider using penalties over rewards.

Your instincts m ...

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

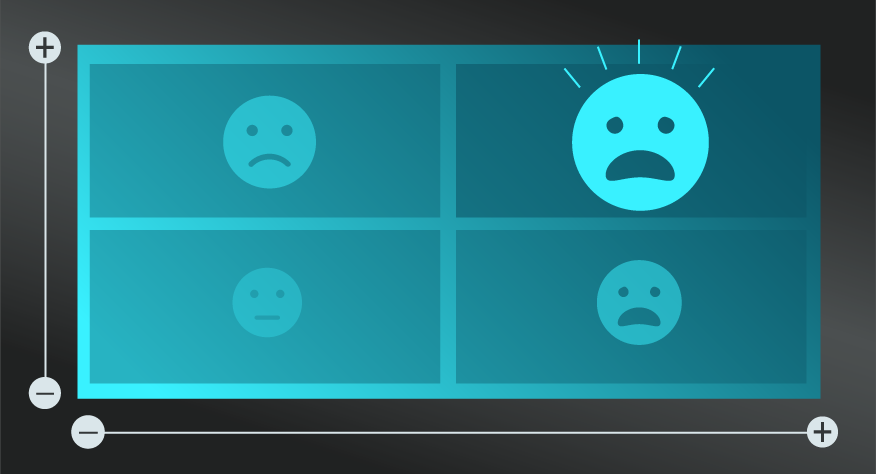

There are a number of studies, including the original ones by Tversky and Kahneman that provide compelling evidence behind Loss Aversion. However, there are also exceptions.

This study found that: “When the outcomes were actually experienced, losses did not have as big an emotional impact as predicted. These authors suggested that the purported asymmetrical impact of losses vs. gains was a property of affective forecasts and not of actual experiences.” In other words, the researchers seemed to argue that what initially presented as Loss Aversion had more to do with emotional responses, which did not always align with losses vs gains.

Other studies have found that Loss Aversion does not seem to arise in repetitive situations or single events with low stakes — indeed the latter phenomenon has been called ‘magnitude dependent Loss Aversion’. Another theory is that Loss Aversion is actually resultant from losses gaining your attention more effectively, so is less about the loss and more about the arousal or focus it initiates. This has been reframed as Loss Attention.

‘Stickk’ to a commitment.

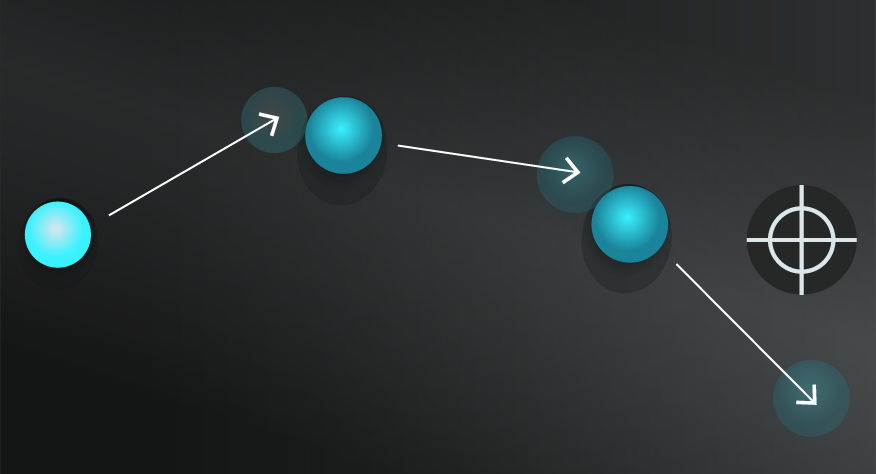

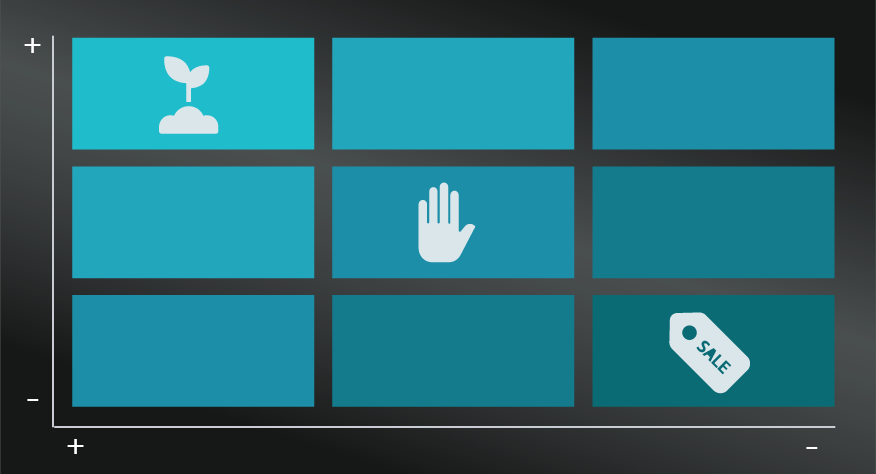

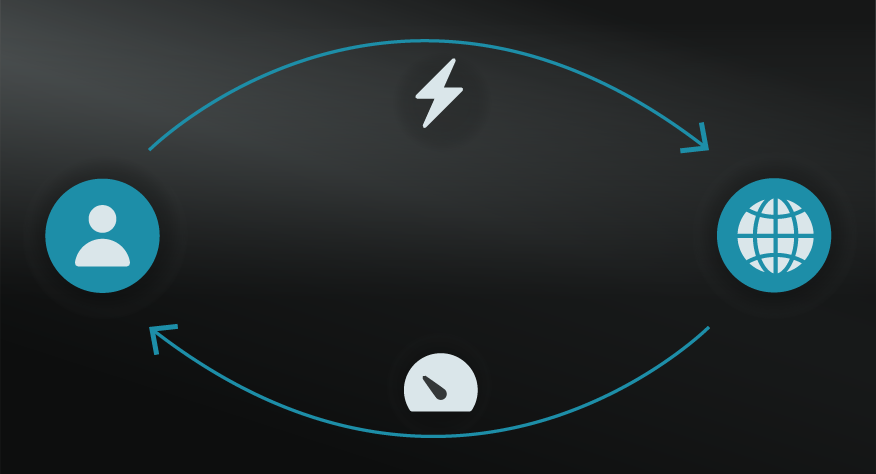

No, that is not a spelling error, this example is about Stickk the web site created by a Professor of Behavioural Economics at Yale University that uses Loss Aversion to help you stick to your behavioural commitments.

Stickk is an online service where you make a public commitment to do something and, if you fail to do it, you will make a donation to a cause or group that you detest. This has proved to be more motivating than rewarding yourself with donating to a group you admire.

Save more tomorrow pension.

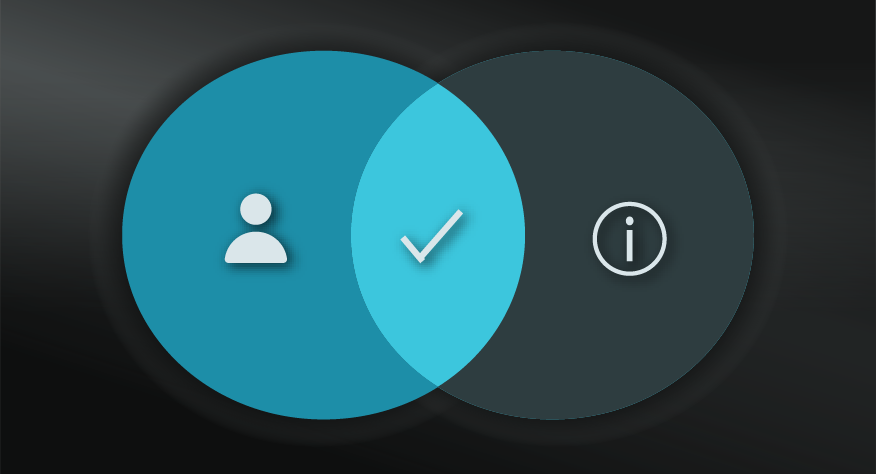

In the book Nudge, Sunstein and Thaler describe the story of the ‘save more tomorrow pension.’ This initiative was designed to encourage young people to invest in pensions using Loss Aversion. The pension plan cost nothing until the individual received a pay rise, and then that pay rise would automatically be directed into their pension fund.

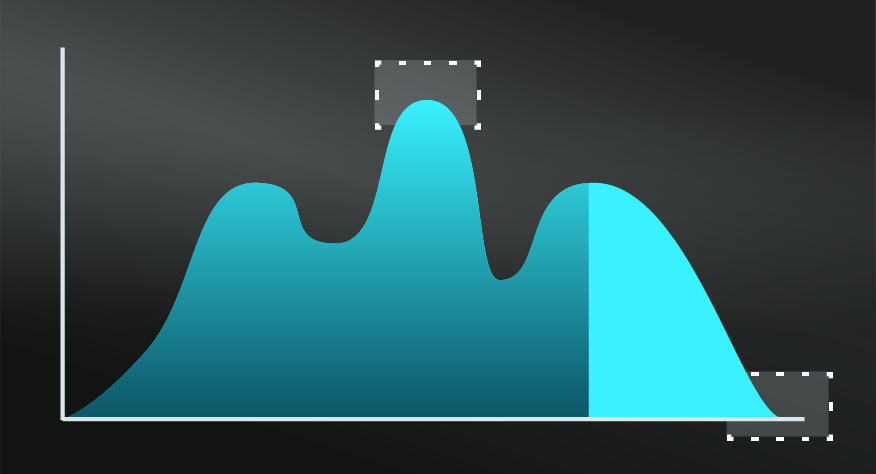

The resultant user experience was that the individual did not see a reduction in their disposable income, there was no loss, there was only less gain. This resulted in a 200% increase in contributions amongst the target group.

Pensions part two — matching payments.

In another initiative linked to pensions, some initiatives have experimented with ‘matching contributions’, so if an individual pays x, the employer would match it. Leveraging Loss Aversion involves paying that match upfront and then taking it away if the individual does not make their payment.

‘No one ever got fired for hiring IBM’.

Have you heard of that familiar business saying? It refers to the fact that if you’re a manager and you hire the predictable ‘safe’ consultants to do work, you will not get fired, even if they don’t deliver results. However, if you go with the innovative, unknown group that might deliver more gains — the risk perception is higher and your job is more at risk as a result. It's essentially a tale in Loss Aversion.

/

Loss Aversion was first identified by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as part of their foundational work behind behavioural economics. The term was coined in 1979 but was more popularised in 1992 when Tversky and Kahneman started to actually measure the asymmetrical nature behind losses versus gain as part of their seminal work on Prospect Theory.

Thinking, Fast and Slow is a mental model that I often reference at ModelThinkers, and it was originally a book that you should definitely dive into for more on Loss Aversion and associated heuristics.

My Notes

My Notes

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”