0 saved

0 saved

19.4K views

19.4K views

Things were better when you were 5-years-old.

According to the research, that’s the age when you most use ...

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

-

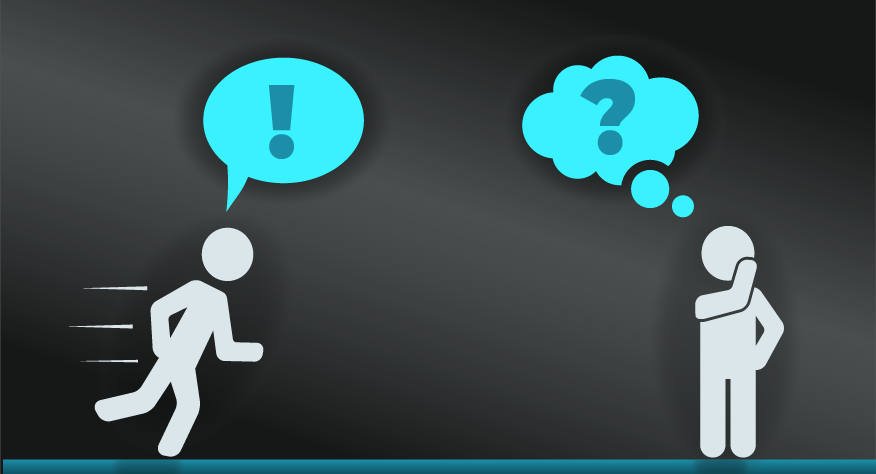

Seperate the task from the solution.

It’s all too ...

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Nulla gravida orci a odio, et viverra justo commodo id. Aliquam in felis sit amet augue laoreet fringilla. Suspendisse potenti. Sed in libero ut nibh placerat accumsan. Proin ac libero euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt. Aenean euismod, nisi vel consectetur interdum, nisl nisi cursus nisi, vitae tincidunt nisi nisl eget nisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Vivamus lacinia odio vitae vestibulum. Nulla facilisi. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nam sit amet erat euismod, tincidunt nisi a, tincidunt nunc. Sed sit amet ipsum non quam tincidunt tincidunt. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel libero nec justo tincidunt tincidunt. Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Integer in libero ut justo cursus tincidunt. Sed vitae libero sit amet dolor tincidunt tincidunt.

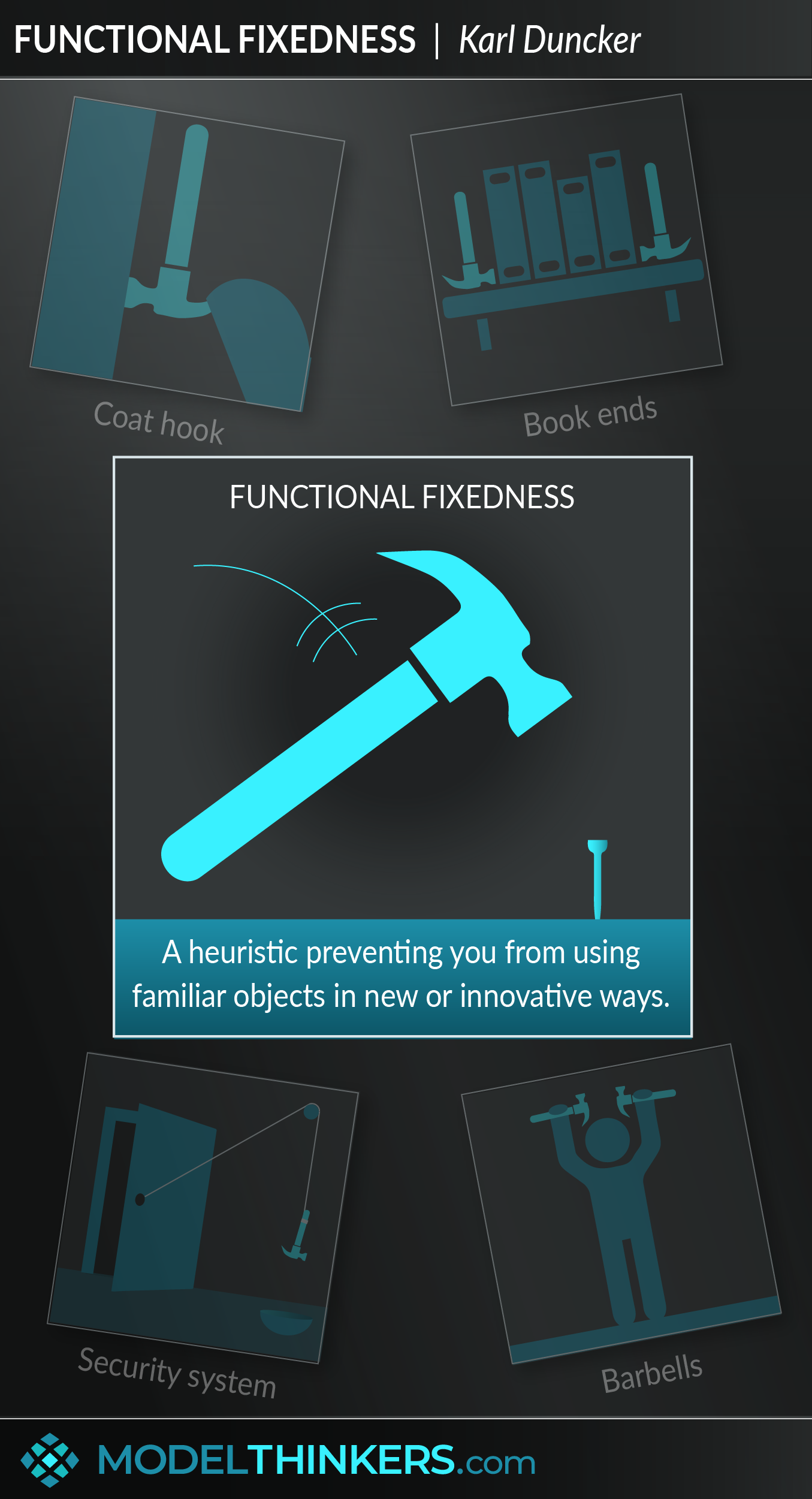

There are few substantial critiques of Functional Fixedness and it is a reasonably accepted heuristic. There have been some debates on nuances — for example, one study claiming that monetary incentives made Functional Fixedness worse, with another unable to repeat that result. But I was unable to find any studies that deny its existence or impact.

Indeed, variations on the Candle Problem persist — with a written version delivered at Stanford University resulting in similar results.

Functional Fixedness was even put to the test with non-industrialised societies to determine the impact of cultural factors — with a recent study conducted within the Amazon region of Ecuador to compare with industrial culture. The results seemed to demonstrate that Functional Fixedness is culture blind and not related to the level of industrialisation or technology of a society.

Adapting during coronavirus.

Much of our world changed during 2020. Many people were left with redundant buildings or businesses that relied on pre-Covid conditions and practices.

Meanwhile, some companies broke through Functional Fixedness to reinvent themselves. A wonderful example of this was the Rubbens gin distillery in Belgium which moved quickly, redirecting its production of alcohol to produce disinfectant by March 2020. Other distilleries around the world soon followed suit.

Breaking Functional Fixedness in tech startups.

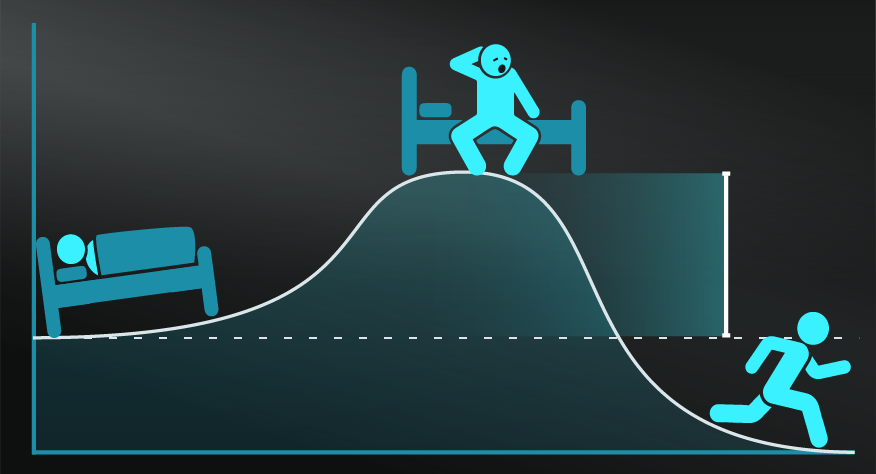

About a decade ago Canadian billionaire Daniel Butterfield, was trying to launch an online game called Glitch. Ever heard of it? Me neither.

At the time the team created an internal messaging system to coordinate their work on the game. It was a little while in before they realised that the messaging system had more value than the game itself — and so Slack was launched.

The Candle Problem.

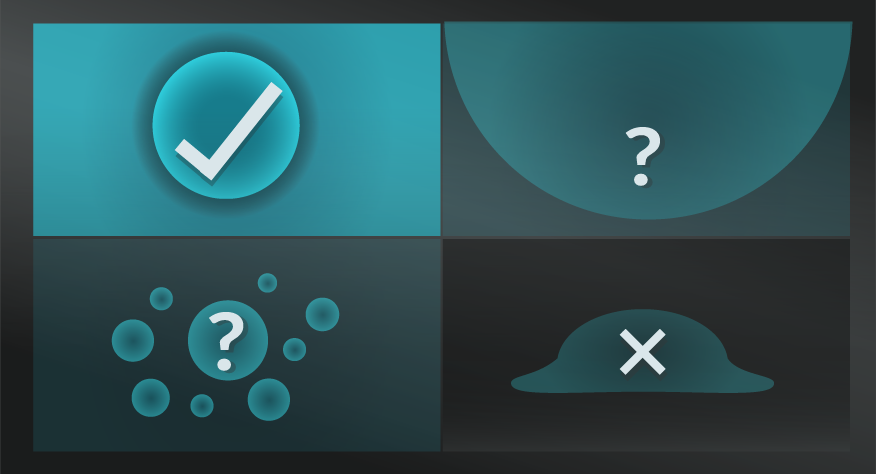

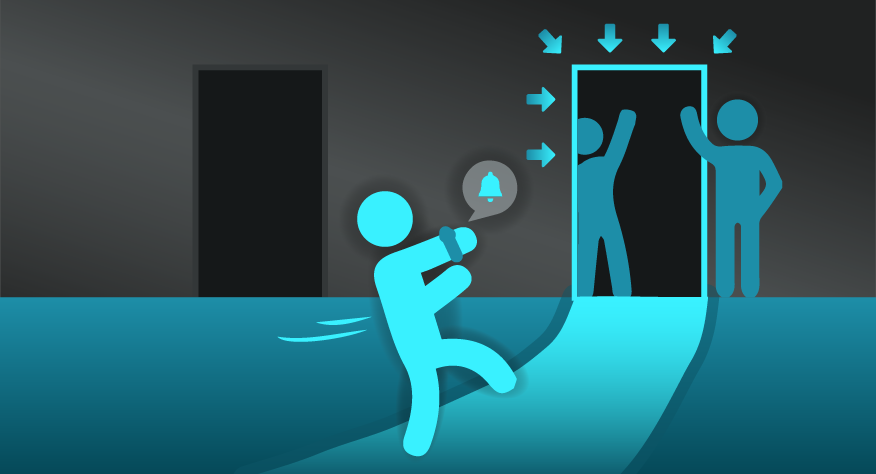

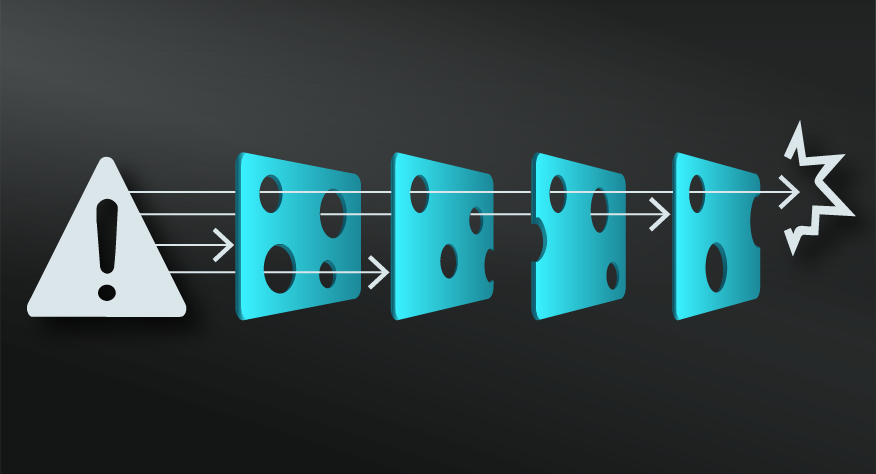

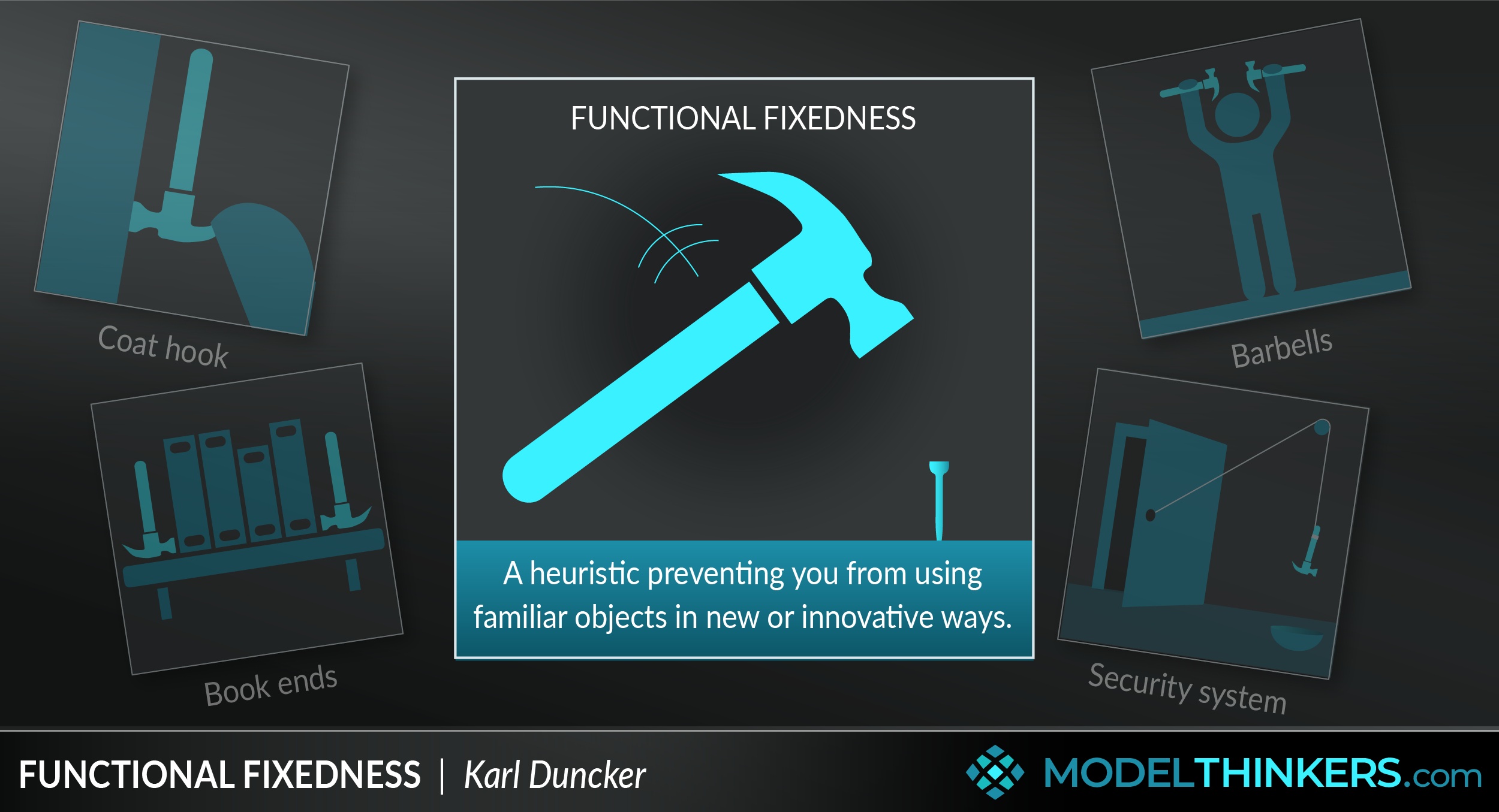

This model is still best described through Duncker’s original Candle Problem from 1945. In the experiment, participants were given the following objects:

-

A box of thumbnails

-

Matches

-

A candle

They were then asked to attach the candle to the wall while ensuring that wax would not drip on the table below once lit. The clock is ticking, how would you solve this problem? Pause for a moment and consider what you would do.

You might try pinning the candle directly to the wall or melting the candle to stick it to the wall. Both would leave the table covered in wax as the candle burnt down. A small proportion of people discovered the real solution.

Meanwhile, another group of participants were given the same task, but were given the following objects:

-

A box

-

Thumbnails

-

Matches

-

A candle

For those playing at home, you’ll notice that the object list is identical to the first one — only this time the thumbnails were not placed in the box.

This subtle change made the ‘box’ an object in itself and a potential part of the solution rather than just a container for thumbnails. It broke the Functional Fixedness related to, dare I say it, ‘in the box thinking.’

This slight tweak resulted in almost all participants solving the problem — simply pinning the box to the wall and placing the candle inside it.

Angels on a pin.

Angels on a Pin is a 1959 essay by American academic test designer Alexander Calandra describing a case where a colleague was about to give a student zero to a Physics question. The question was ‘Show how it is possible to determine the height of a building with the aid of a barometer.'

The student's answer was to tie the barometer to a rope, lower the rope and measure the resulting distance. Technically correct, but not the physics assessment they were looking for.

The academics decided to give the student another chance, asking them to demonstrate knowledge of physics in their next attempt. The student’s second answer was to drop the barometer from the top of the roof and time how long it took to hit the ground, then use the formula S = 0.5at squared to calculate the height.

The student was able to offer several other options including measuring the barometer versus building shadows, creating a pendulum with the barometer and comparing gravity at the different heights, or offer the barometer to the superintendent if he revealed the height of the building.

All of the answers continued to expose the Functional Fixedness of the academics who crafted the original question.

d

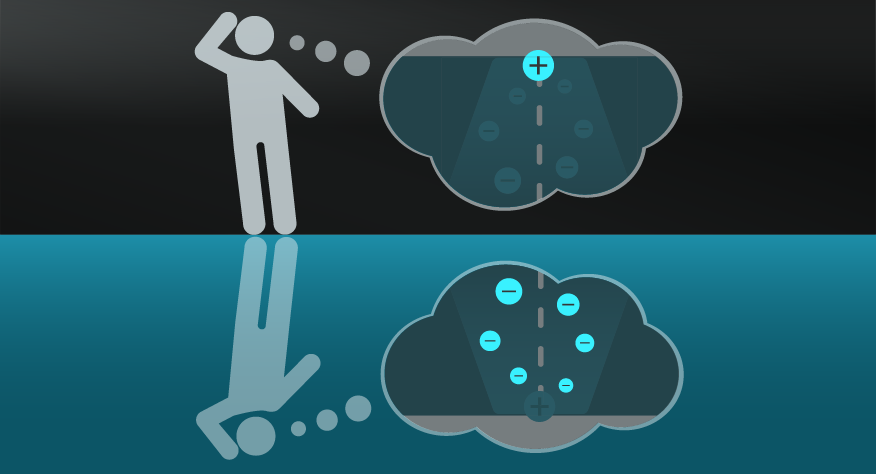

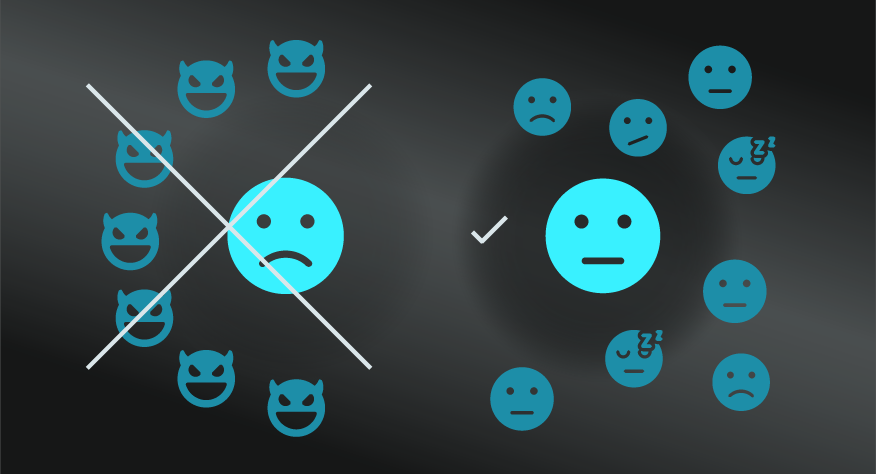

The term Functional Fixedness was coined by Karl Duncker in 1945, who described it as a “mental block against using an object in a new way that is required to solve a problem.” His original study involved the Candle Problem, outlined in the overview above.

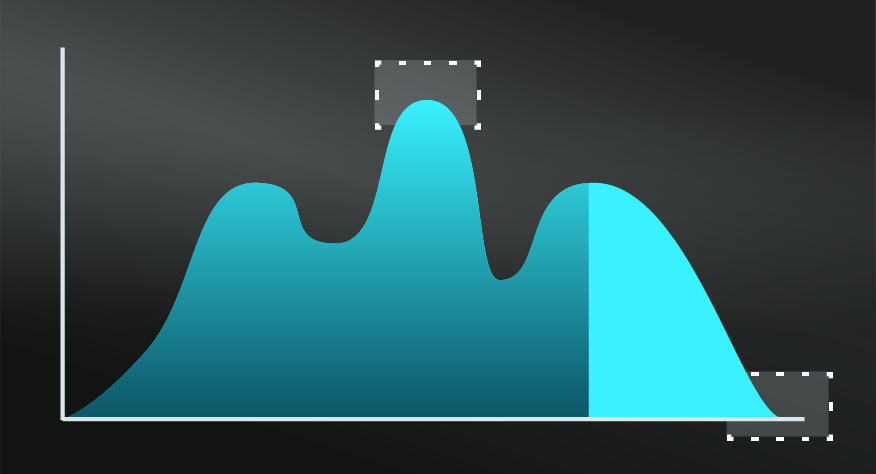

This Candle Problem, in many ways, has become a de facto test of creative insights, leading to the 2009 study by William Maddux and Adam Galinsky to assess the impact of travelling and living overseas on creativity — they concluded that a period spent adjusting to living (not just travelling) abroad did increase creativity.

My Notes

My Notes

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”